<< Hide Menu

Puritans, Again? In Defense of The Scarlet Letter

8 min read•july 11, 2024

Kristie Camp

Kristie Camp

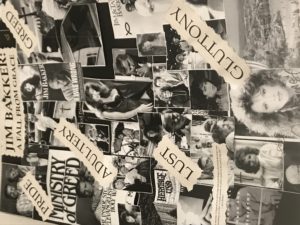

An old project from a student from our reading of THE SCARLET LETTER, making a connection between Dimmesdale and Jim Bakker.

In Defense of The Scarlet Letter

If you will, please allow me a moment to stick my foot into a raging river of debate among high school English teachers, and I pray that my foot won’t end up in my mouth later.

A swirling, muddy eddy has formed from conversations about the use of independent texts versus whole-class novels, and along with that debate, the one centered on modern (possibly Young Adult) texts versus classic novels. Research has shown that we need to make some moves toward independent reading and modern texts. And, of course, I agree with that research.

It is true that students should read and are more likely to read texts they choose from themselves. Yes, students need to see themselves represented in the texts they read. (Cultural diversity in our texts matters; see this article from Dr. Alfred W. Tatum.) And yes, finding texts students can read and understand independently improves their reading fluency and comprehension. Therefore, should we incorporate Young Adult literature and independent reading into the high school ELA classroom? Yes. Absolutely. (For more info about recommendations for adolescent literacy, see this PDF from the International Reading Association.)

These findings seem so strong and clear that some professionals advocate eliminating all whole-class texts and all classic novels from our contemporary class altogether and moving toward a totally independent, self-selected reading curriculum. I am not ready to take that step for several sound reasons, and I hope to be able to share with you a reasonable compromise over the next few entries here on my Fiveable blog.

The high school ELA classroom has room for a whole-class text along with independent texts, and I may examine that balance later, but for right now, I would like to start with a defense of the use of whole-class, classic novels in the modern ELA classroom. In fact, I would like to defend one classic novel, The Scarlet Letter, by Nathaniel Hawthorne, specifically, but my defense of it could be applied to another great piece of literature an ELA teacher may choose, if it is taught well.

So, first, a discussion of why The Scarlet Letter is still relevant, and then the next blog will discuss what makes a classic novel work in the modern classroom, and finally, a third entry on why we shouldn’t abandon whole-class texts altogether.

Disclaimer: I have experienced much success teaching The Scarlet Letter; it is a personal favorite of mine. I think those two truths make it a viable text for my classroom, so my selection of this text to discuss and to teach is completely personal, but as I will explain, that personal connection feeds my reasoning for using it in my class, which is why I have chosen to discuss it here and now.

Haters Gonna Hate

Over my 22 years in secondary English education, I have heard countless attacks on The Scarlet Letter, ranging from how it is irrelevant in the modern world to the fact that the text’s difficulty makes reading it too much of a chore for the modern student who is easily bored and will not fight his or her way through the thick syntax and unknown words. In fact, one year, our district office hosted an assembly for all the district’s teachers, and the guest speaker brought in students to talk about their reading preferences. They all said they would gladlyread in class if they could read what they wanted (and again, the research backs this up) but then one student said something like this: “Why are we reading things like The Scarlet Letter when no one really cares about women having babies out of wedlock anymore?”

The audience erupted into “ooohhhs” and “aaahhhs.” Everyone who knows me turned to look at my reaction, and I even heard some people say, “Where is Mrs. Camp?”. Thank goodness, the girl on stage who made the comment was not one of my students; I am not even sure she was a student at my school. During the students’ on-stage conversation, teachers commented on a back channel, and the responses from the teachers were posted on a huge bulletin board on stage for the participants to read and respond. So, I typed into the back channel: “If all a student knows about The Scarlet Letter is about an unwanted pregnancy, either the teacher didn’t teach it well, or the student didn’t read the whole book.”

Again, the “oooohhhs” and “aaahhhs.”

The How and Why

I stand, to this day, firmly resolved, that if a classic is taught well, it can engage teen readers as well as or better than a modern, YA novel. The secret lies in the teaching. (Doesn’t it always?) Throwing the book at students and telling them to read it will only result in frustration and failure. But if a classic is worthy of the label, then it should reach deep into the heart of who we all are as humans, and The Scarlet Letter is truly a classic that resonates today.

First, let me establish that The Scarlet Letter is about so much more than an unexpected pregnancy. While the book may open with the public shaming of Hester Prynne because of her giving birth out of wedlock, the book doesn’t even discuss the morality of that situation much more after the opening scene. The story uses this situation as a springboard to dive into the morality of and lessons learned from public shaming, hypocrisy, revenge, lies, and social isolation. It is a rather sophisticated study of self-harm and a revealing look at gaslighting as a form of abuse in relationships. While the time period and situation may seem foreign to our students, the issues presented are as close to them as their next Snap Chat post.

Here are just a few reasons The Scarlet Letter is completely relevant to students in 2019.

1. Public Shaming is more real than ever as a result of social media.

Teens live painfully public lives as a result of social media. A social faux pas can live forever thanks to Instagram and Twitter, and what may have been shared among hometown folks in gossipy stories can now be shared among the entire world. Reporters and researchers are documenting the effects of social media shaming as fast as they can, but the examples roll in faster all the time (Here are a few stories on public shaming on social media: story 1; story 2; story 3).

Hester endures three hours on the scaffold where everyone in town looks at her in stony silence, but that moment isn’t so different from the video that goes viral – a video that shows someone saying or doing something they later regret. I don’t have to look far to make the opening chapters of The Scarlet Letter completely relevant to my students, but I do so through Jon Ronson’s Ted Talk and a social experiment of my own that I will explain in blog #2 in this series. Modern students have to stretch very little to sympathize with Hester’s situation, even if she is there for a reason we, as a society, might not shame any longer (but I am not sure that is true, either).

2. Hester Prynne is a model of strength and empowerment.

The way Hester handles the public shaming and ends up triumphing over the public shaming is what makes her a modern hero. What seems unbearable – to lower her head and go about lowly duties of feeding and clothing the poor who scorn the hand that aids them – becomes the very badge that allows her access to a world she would have never known. A world of sorrow and pain? Yes, but also a world where she can work real and meaningful good, a world where she knows her presence matters and brings healing into a community so dark that the governor embeds broken glass into his stucco walls for a momentary speckle of light. In fact, in the very chapter where we see the ironic sparkly glass of the governor’s mansion, we also see Hester’s determination as a woman demanding her rights as a mother. In chapter seven, Hawthorne says she doesn’t hold back when the bond servant refuses her entry: “Nevertheless, I will enter,” Hester says, and she does. Like Preacher Ellen, played by Viola Davis, in Madea Goes to Jail, Hester learns that her tragic experiences allow her to be trusted by others embroiled in their own tragedies, and this creates a hero. Hester becomes known for her amazing abilities instead of her shame, and her legacy is one of empowering younger women, offering them advice and strength as she grows old in wisdom, promising of a better day to come. Hester can serve as a worthy model of countless values: strength, resilience, charity, determination, forgiveness, love, and more.

3. We are all hypocrites, and social media has heightened our hypocrisy.

One of the enduring emblems of The Scarlet Letter is its indictment of hypocrisy. From the church, yes, in the form of the miserable Minister Arthur Dimmesdale, but just as vehemently from the governor, other social leaders, and the “good people” of the town, “church-members in good repute.” Hester learns quite early (chapter 5) from her ordeal with the letter on her chest that everyone wears a letter; they have just been able to keep theirs hidden more than she was able to. Yet, her knowledge of the “hidden sin in other hearts” is what makes Hester more compassionate and empathetic, not hardened or resentful. If we have learned one truth from our experiences with social media, it is that most of us are only interested in posting our best photos, the ones Photoshopped to perfection, the ones showing us having a great time with great friends, the ones of the beach sunset or Starbucks break or workout success. None of us want our ugly truths out for everyone to criticize, and none of us want to face the horrible wrath of social media shaming. The cruel cycle of presenting our own acceptable persona, hiding the dark truths of our real nature, and shaming those who can’t hide their sins hasn’t changed much at all since Puritan America. Same story, just different tools.

Here are just three simple but solid reasons The Scarlet Letter is a relevant text for modern teens. Is it difficult to read? Sure. Is it worth the class time it takes to teach it? Well, that depends. We’ll explore that idea next entry. See you soon!

⚡ Related Articles

© 2024 Fiveable Inc. All rights reserved.