<< Hide Menu

Unit 1 Overview: Pitch, Major Scales and Key Signatures, Rhythm, Meter, and Expressive Elements

10 min read•june 18, 2024

1.1: Pitch and Pitch Notation

Reading Notes on a Staff

The first thing that we will learn in this course is how to read music written on the staff. One staff contains 5 lines and the spaces between those lines are also significant. The grand staff is a series of two staves, which are used to notate pitches that come from a wide range of voices. The grand staff consists of two clefs: the treble clef and the bass clef.

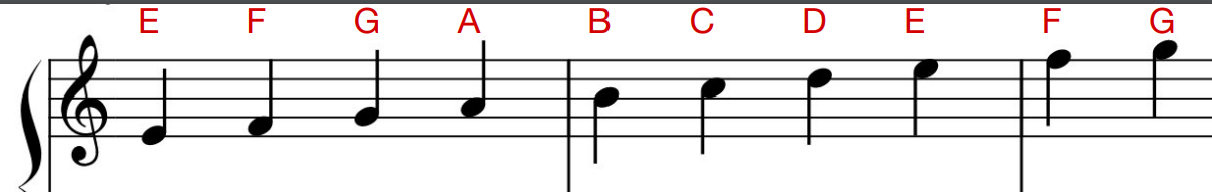

Here are the pitches of the lines of the treble clef:

The bottom line on the treble clef is an E. The space right above that is an F. The next line is a G. We read the first three notes of this example as E-F-G. You might already see a pattern here! For each line and subsequent space, we go through the alphabet. What happens when we get to G? We start over again at A. The fourth note is A, the 5th note is a B, and the 6th note is a C. See how that works?

There are several ways to remember all the different lines and spaces on the treble clef. Many people use a mnemonic device to remember the order of the lines (E-G-B-D-F). For example, the age-old sentence is: "Every Good Boy Does Fine."

The spaces on the treble clef spell one easy word: FACE!

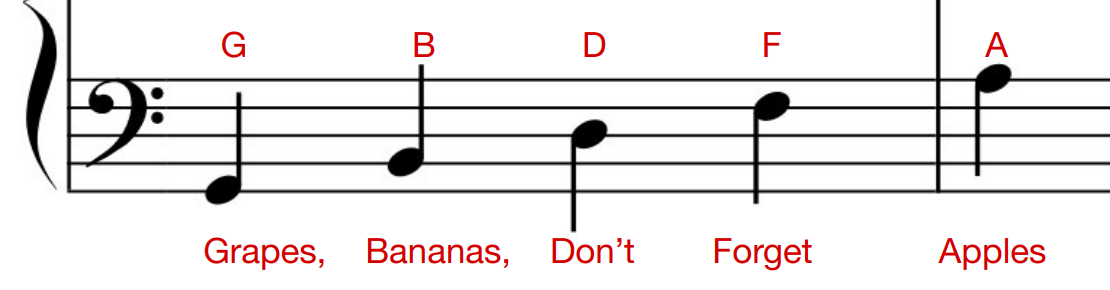

On the bass clef, the lowest line is a G, and the lowest space is an A. Here are some ways to remember the bass clef lines (G-B-D-F-A):

- "Good Birds Don't Fly Away"

- "Go Buy Donuts For Al"

- "Grapes, Bananas, Don't Forget Apples"

- "Good Boys Do Fine Always"

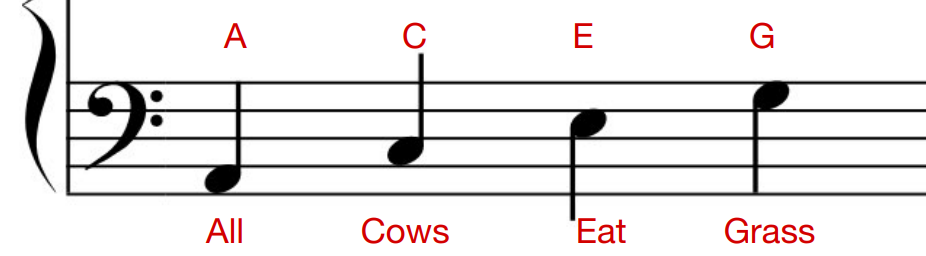

Last, but not least, we have the spaces on the bass clef (A-C-E-G)

Accidentals

Accidentals alter pitches by a half step. The sharp ♯ indicates that a pitch will go up by one half step. The flat ♭ indicates that a pitch will go down by one half step. And, the natural ♮ cancels any flat or sharp that a pitch may have had.

Measures

Notes are organized into measures. The vertical line that spans between the treble and bass clefs indicate the end of a measure. Sometimes measures are called bars. The line can also be called a bar line.

1.2: Rhythmic Values

The beat is the most basic unit of time in a measure. Some notes can take up multiple beats, and others will take up only a portion of a beat.

The number of beats per measure depends on the time signature. The time signature not only determines how many beats there are per measure, but it also tells you which note value gets counted as one beat. For simplicity's sake, however, we'll just assume that a quarter note is one full beat for now.

Beats are important to know in music because they help us organize the rhythmical symbols. These are called quarter notes. Each quarter note has a value of 1 beat.

If you divide a quarter note in half, you get an 8th note. This means there are two 8th notes for every quarter note beat.

If you divide an 8th note in half, you get a 16th note.

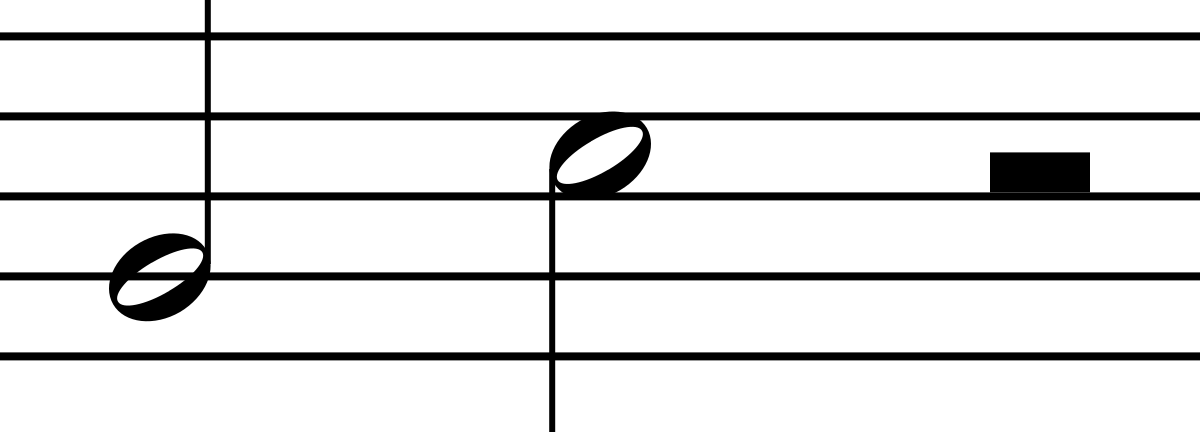

There are also half notes and whole notes. A half note takes up two beats. A half note looks just like a quarter note, but with an open circle instead of a full circle.

Whole notes take up 4 beats, and they are just one open circle with no stem.

Each note value has a corresponding rest, which tells us to pause for that amount of time. There are quarter rests, eighth rests, sixteenth rests, half rests, and whole rests.

1.3: Half Steps and Whole Steps

Imagine that you are sitting in front of a piano or a keyboard, and you play every single note, black or white, in order. You might play A-Bb-B-C-C#-D-Eb-E-F-F#-G-G#-A. This is called the chromatic scale. Notice that not all of the transitions have accidentals. For example, B# is enharmonically equivalent to C natural, and E# is enharmonically equivalent to F natural.

A chromatic scale is special because all of the notes are a half step apart. In other words, these notes are right next to each other on the keyboard. For example, C is a half step away from C#, and E is a half step away from F.

A whole step is just two half steps. C is a whole step away from D, and E is a whole step away from F#, for example.

1.4: Major Scales and Scale Degrees

When we arrange certain pitches in a specific ascending or descending pattern of whole steps and half steps, we call that a scale. Western music is comprised of major and minor scales. There are many other types of scales that are used in other parts of the world.

How do you create a major scale? Let's first see what it looks like.

This is a C Major scale. It starts on a C, and ends on a C. A scale will always end on same note an octave higher (or lower). An octave is an interval of 8 pitches. We usually write major scales (and chords) using capital letters.

There is a very specific space between each pitch in a major scale: whole step-whole step-half step-whole step-whole step-whole step-half step. You don't really have to memorize this. You can just try deriving it from the C Major scale (the C major scale has no accidentals), or you can memorize which sharps and flats each major scale has. This is why the major scale is also known as the diatonic scale -- it is made up of five whole steps and two half steps, which are also known as "tones" and "semitones" respectively.

When we are writing in a certain key, for example C Major, we say that we are "in C Major." You can imagine all the notes that are a member of C Major as being in the key, and all the notes that are not a member of C Major as being out of the key. For example, D is in C Major, and D# is not in C Major. Another way to say this is to say that D is diatonic, and D# is chromatic.

The starting pitch of a major or minor scale is called the tonic. Each pitch is considered to be a degree of the scale, and each scale degree has a special name. For example, in a C Major scale, the first scale degree is C, the second scale degree is D, and so on. Each scale degree has a special name that is indicative of its role in the key.

The degrees of a scale, in order, are the tonic, supertonic, mediant, subdominant, dominant, submediant, and leading tone. They correspond to the seven scale degrees of a major or minor scale.

The major scale degrees are often abbreviated using Roman numerals, with uppercase numerals representing major chords and lowercase numerals representing minor chords. For example, the tonic of a C major scale would be represented as "I," the dominant would be represented as "V," and the submediant would be represented as "vi."

1.5: Major Keys and Key SIgnatures

When the majority of a musical passage congregates around the pitches of a major or minor scale, we consider it to be within a certain key. For example, if the notes of an F major scale are used and F is considered a central pitch, the piece of music is referred to as "in the key of F major".

The key signature is placed on the same line as the treble clef and the time signature, and it appears immediately after the clef and time signature. It consists of one or more sharp or flat symbols, placed in a specific order, that indicate which notes are to be played as sharp or flat.

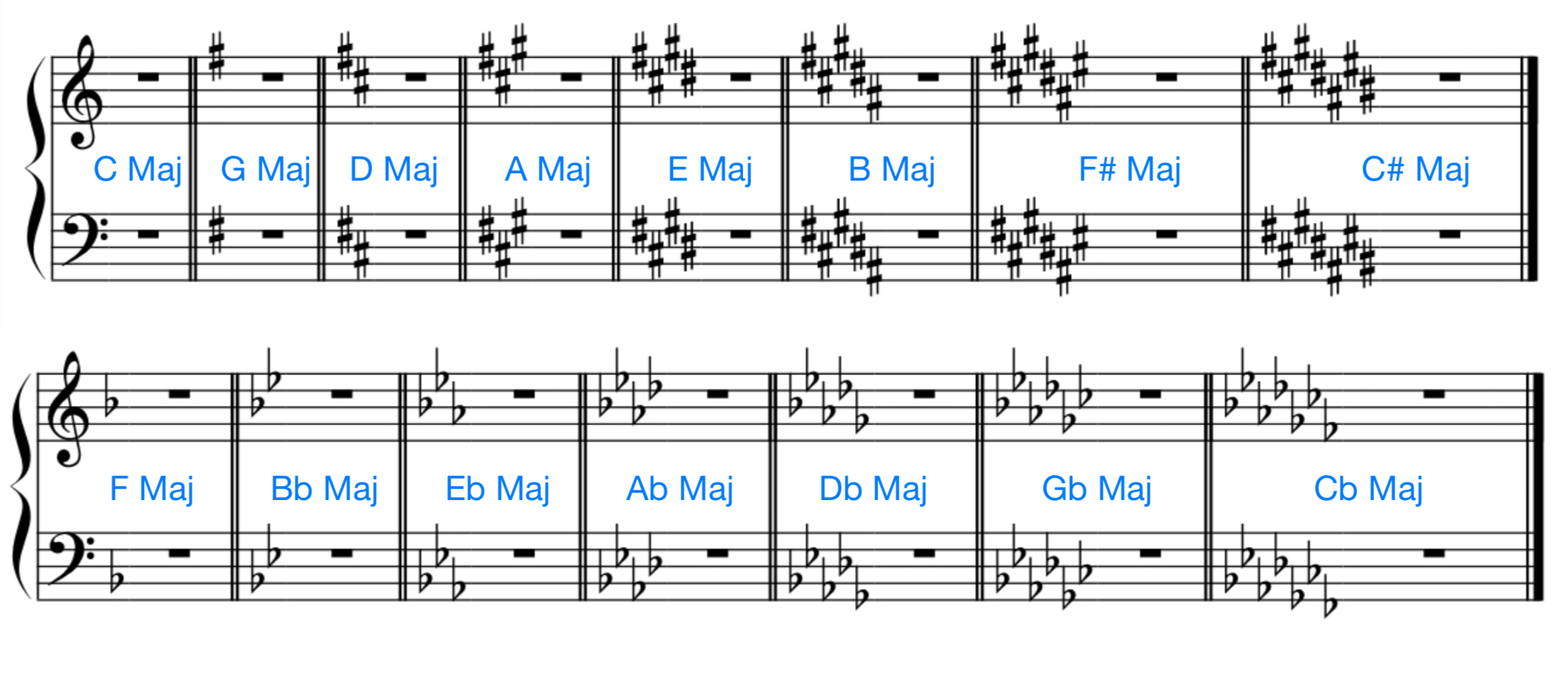

Below are all of the different key signatures. Note that Maj is short for major—you may frequently see that abbreviation.

1.6: Simple and Compound Beat Division

In music theory, meter refers to the rhythmic structure of a piece of music, or the pattern of strong and weak beats within a measure. Usually, we notice that there are many different ways you hear the pulses of music, or the "beat" of a piece. The largest structure (arguably) is the measure.

All the beats inside the measure are considered the beat, and it's another way to count the pulses in music. The number of beats in a measure depends on the time signature and the type of meter (simple vs. compound).

Simple meters are meters where most of the beats are divided into twos. A good heuristic is that if the bottom number on the time signature is 4, then it will be a simple meter. For simple meters, the top number of the time signature tells you how many beats there are per measure. For example, a time signature of 4/4 indicates that there are four beats per measure, and a quarter note receives one beat.

Compound meters, on the other hand, are meters where beats mostly divide into threes. If you've ever played music in 6/8 time, you might notice that there are supposed to be 6 "beats" per measure according to the time signature, but really, it sounds like two big beats per measure, where each beat is divided up into three smaller beats. This is an example of compound meter.

1.7: Time Signatures

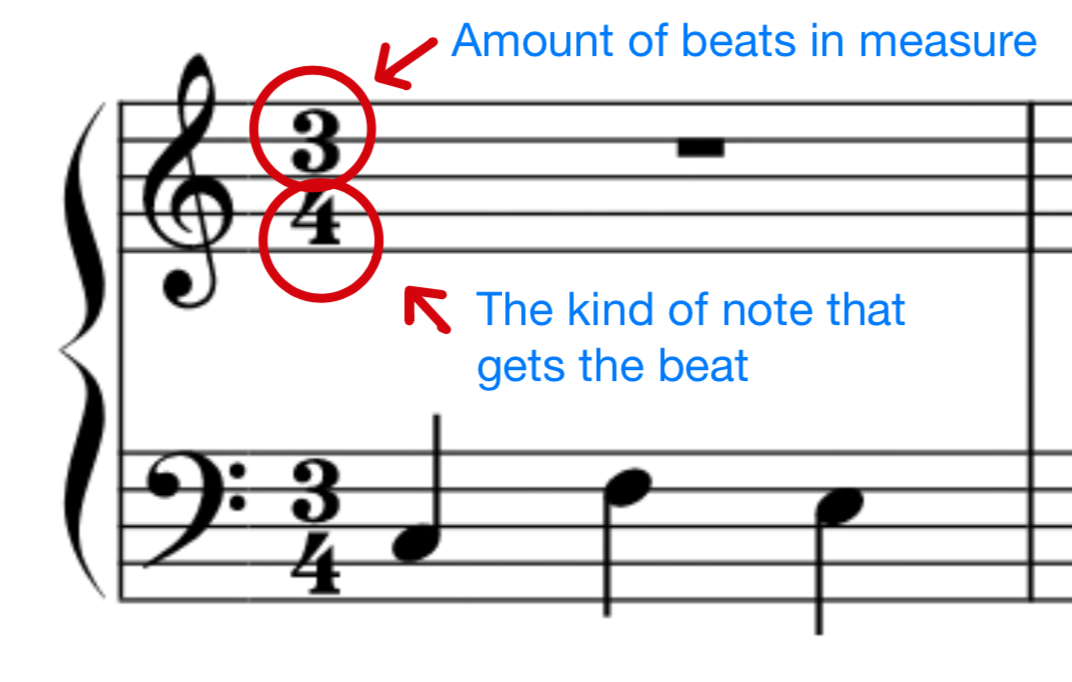

The time signature shows us the relationship between the number of beats in a measure and the type of beat that is used. The top number gives you the number of beats or beat divisions per measure, and the bottom number gives you which note is counted as one beat or beat division.

In addition to classifying meters as simple and compound, we can also classify them as duple, triple, and quadruple. In short, duple meters have 2 beats per measure, triple meters have 3 beats per measure, and quadruple meters have 4 beats per measure. Remember, there are beats -- not beat divisions. Examples of duple meters are 2/4, 2/2 and 6/8, examples of triple meters are 3/4, 3/8, and 9/8, and examples of quadruple meters are 4/4 and 12/8.

1.8: Rhythmic Patterns

In music, a rhythmic pattern is a series of rhythms that are repeated in a specific order. These patterns can be created using a variety of techniques, such as the use of different time signatures, rhythms played on different instruments, or the use of syncopation.

Rhythmic patterns are an important aspect of music and play a role in determining the feel and groove of a song. They can also be used to create a sense of unity and structure in a piece of music. Rhythmic patterns can be simple or complex, and can be used in a variety of musical styles.

For example, a simple rhythmic pattern might consist of just a few basic rhythms played in a repeating pattern, while a more complex pattern might involve multiple rhythms played simultaneously on different instruments.

1.9: Tempo

Tempo explains the speed of the beat in music. It is typically measured in beats per minute (bpm) and indicated at the beginning of a piece of sheet music with a metronome marking. The tempo of a piece of music can affect its mood and can vary widely, from slow and solemn to fast and energetic.

The most widely-used Italian tempo indicators, from slowest to fastest, are:

- Grave—slow and solemn (20–40 BPM)

- Lento—slowly (40–45 BPM)

- Largo—broadly (45–50 BPM)

- Larghetto—rather broadly (60-66 BPM)

- Adagio—slow and stately (literally, “at ease”) (66–73 BPM)

- Andante—at a walking pace (73–77 BPM)

- Andantino—slightly faster walking pace (78–83 BPM)

- Moderato—moderately (86–97 BPM)

- Allegretto—moderately fast (98–109 BPM)

- Allegro—fast, quickly and bright (109–132 BPM)

- Vivace—lively and fast (132–140 BPM)

- Presto—extremely fast (168–177 BPM)

- Prestissimo—even faster than Presto (178 BPM and over)

You must know these terms for the AP Music Theory test! Note that while the beats per minute are given for each of the tempo markings, they are not hard and fast rules. Instead, think of tempo markings as feelings or moods that you want to encapture. For example, Andante or Andantino is in fact slower than Vivace, but a piece in Andante is also more casual, laid back, and measured because pieces in Andante want to capture the feeling of "walking".

1.10: Dynamics and Articulation

Dynamic markings show how loud or soft the music ought to be played. They range from very soft (pianissimo), to very loud (fortissimo).

We use the < symbol to denote a crescendo, which means to increase the volume over the space indicated, and the > to denote a decrescendo, which means to decrease the volume. Sometimes, decrescendos are called diminuendos, and abbreviated "dim." on a score.

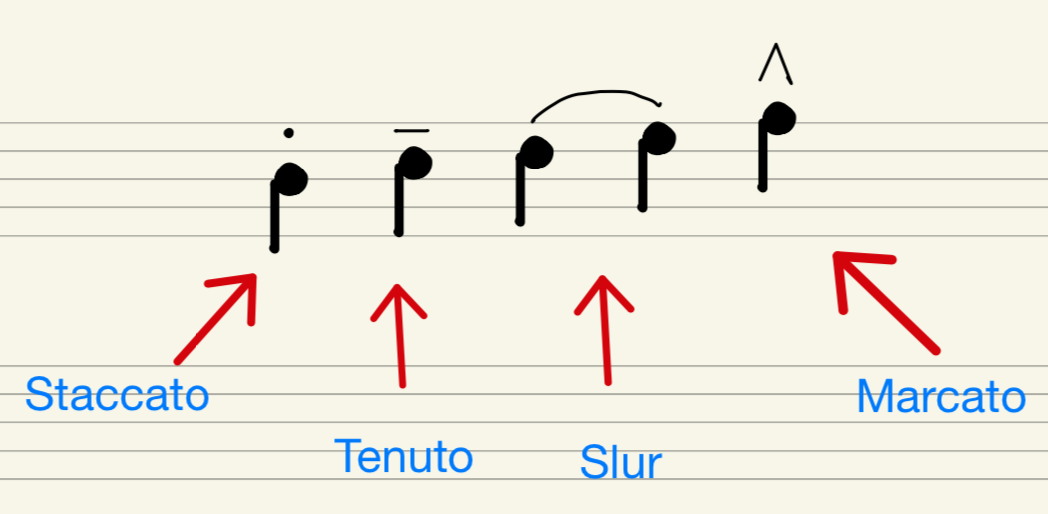

Composers may also want their music to be played with certain articulation. Articulation refers to the way that individual notes are played or sung in a piece of music. It can affect the phrasing, tempo, and overall character of the music, and it is an important aspect of musical expression.

Common articulations are “staccato,” “tenuto,” “legato,” and “marcato.”

© 2024 Fiveable Inc. All rights reserved.