<< Hide Menu

2.2 Relative Keys: Determining Relative Minor Key and Notating Key Signatures

4 min read•june 18, 2024

Mickey Hansen

Mickey Hansen

Major and Minor Modes

Within pieces of music, tonality, or keys, can shift between different keys within major and also shift to minor keys. Many songs or pieces of music do this! Sometimes we refer to either major or minor as a mode. There are other types of modes, but we won't discuss those until Unit 8.

For example, if a piece of music shifts from G major to G minor, this would be considered a "change in mode."

On the aural portion of the AP® Music Theory test, you will NOT be required to identify the letter name of a key simply by ear, blindly. Nowhere in the APMT test will you required to have absolute pitch, aka "perfect pitch."

You WILL, however, be tested on relative pitch, which all musicians will develop with time. For example, you may have to listen to a piece of music and identify if a section changes from major to minor. You wouldn't have to identify by ear that it changes from A major to F# minor.

🦜 Polly wants a progress tracker: Listen to the following excerpt of this piece by Chopin. When does it change tonalities?

Parallel and Relative Keys

Parallel keys are musical keys that have the same tonic, or root pitch, but are written in different modes. For example, the key of C major and the key of C minor are parallel keys, because they both have C as their tonic pitch.

In general, there are two pairs of parallel keys: major and minor, and dorian and mixolydian. The major and minor keys are considered parallel because they share the same tonic pitch and have a similar tonal structure, with the major key being characterized by a brighter, more joyful sound and the minor key by a darker, more introspective sound. We'll learn about dorian and mixolydian later. For now, let's focus on major and minor relative keys.

Parallel keys can be used to create smooth transitions between different sections of a piece of music, or to create contrast and variety. They are an important aspect of tonal music and are used in a variety of musical styles.

If we have a major key, and we want the parallel minor, we just flat the 3rd, 6th, and 7th scale degrees. Notice that sometimes, major keys with sharps have parallel minors in flats. For example, consider D Major. If you flat the 3rd, 6th, and 7th scale degrees, you get F natural, Bb, and C natural. So, the key signature for d minor has one flat.

Relative keys are musical keys that share the same key signature, meaning they have the same pitches, but have a different tonic, or root pitch. For example, the key of C major and the key of a minor are relative keys, because they have the same pitches but their tonic pitches are different.

Relative keys are related by a distance of a minor third. The tonic of the major key is a minor third above the tonic of the relative minor key. For example, the tonic of D major is a relative third above the tonic of b minor. Therefore, C major and a minor have the same key signature.

🦜 Polly wants a progress tracker: What's the relative minor for Ab Major? Write the key signature of this minor key.

Minor Key Signatures

There are three main types of minor keys: natural minor, harmonic minor, and melodic minor. Each type of minor key has a different key signature and a unique musical character.

In a natural minor key, we get the key signature from the relative major key. For example, if we want to write in c minor, then we know that the relative major is Eb Major, so there must be 3 flats: Bb, Eb, Ab.

We always write the key signature in natural minor, even if we sometimes want to sharp the 6 and/or the 7 in our music. We save these sharps for accidentals. One of the reasons why this is the case is that it is awkward to have both sharps and flats in a key signature.

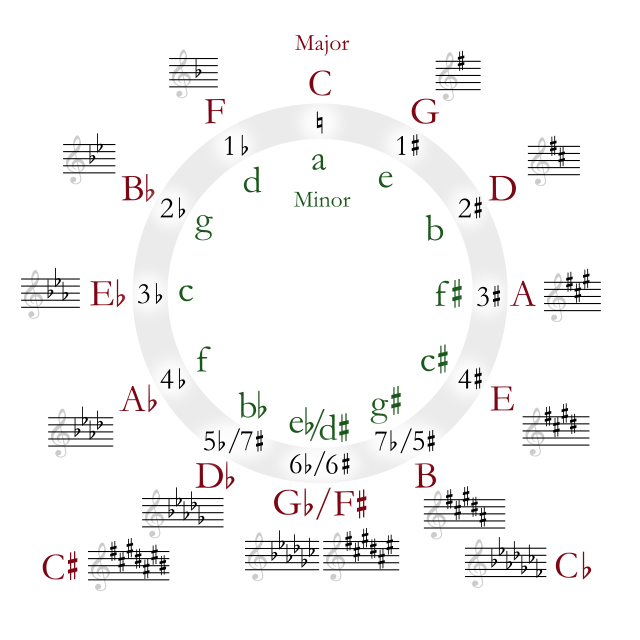

The Circle of FIfths for Minor Keys

You can also use the circle of fifths to determine minor key signatures. All you have to remember is that a minor has no accidentals. Going clockwise around the circle of fifths starting at a minor, you get e minor, b minor, etc. As such, e minor has one sharp (F#), b minor has two sharps (F# and C#), and so on.

Going counterclockwise around the circle of fifths, you have d minor, g minor, etc. Therefore, d minor has one flat (Bb), g minor has two flats (Bb and Eb), and so on. Notice how the order of sharps and flats are the same for both major and minor keys!

Here is the circle of fifths for reference:

© 2024 Fiveable Inc. All rights reserved.