<< Hide Menu

Unit 2 Overview: Music Fundamentals II (Minor Scales and Key Signatures, Melody, Timbre, and Texture)

12 min read•june 18, 2024

Sumi Vora

Sumi Vora

2.1: Minor Scales: Natural, Harmonic, and Melodic

Just like in major scales, each minor scale has a certain pattern of whole and half steps. There are three types of minor keys: natural minor, harmonic minor, and melodic minor.

The natural minor scale has a distinct sound that is often described as sad, serious, or melancholy. It has the pattern: whole step-half step-whole step-whole step-half step-whole step-whole step. This means that if you want the parallel natural minor given a major scale, all you have to do is flat the 3rd, 6th, and 7th scale degrees!

You can also build a natural minor scale by starting on the sixth degree of a major scale and using the same notes.

If you take a natural minor scale and you sharp the 7th scale degree, you get the harmonic minor scale. This is probably the minor that you're most used to hearing. We usually sharp the leading tone because our ears like to hear the half step between the seventh scale degree and the tonic - we are "led into" the tonic, giving us a good resolution to the scale.

The melodic minor scale goes one step further and sharps both the 6th and the 7th scale degrees of the natural minor scale. However, this only happens on the way up. When you play the descending melodic minor scale, it is the same as the descending natural minor scale.

Most pieces use the natural minor, harmonic minor, and melodic minor interchangeably throughout the piece, depending on the function of each note. The key signature is always the key signature of the natural minor.

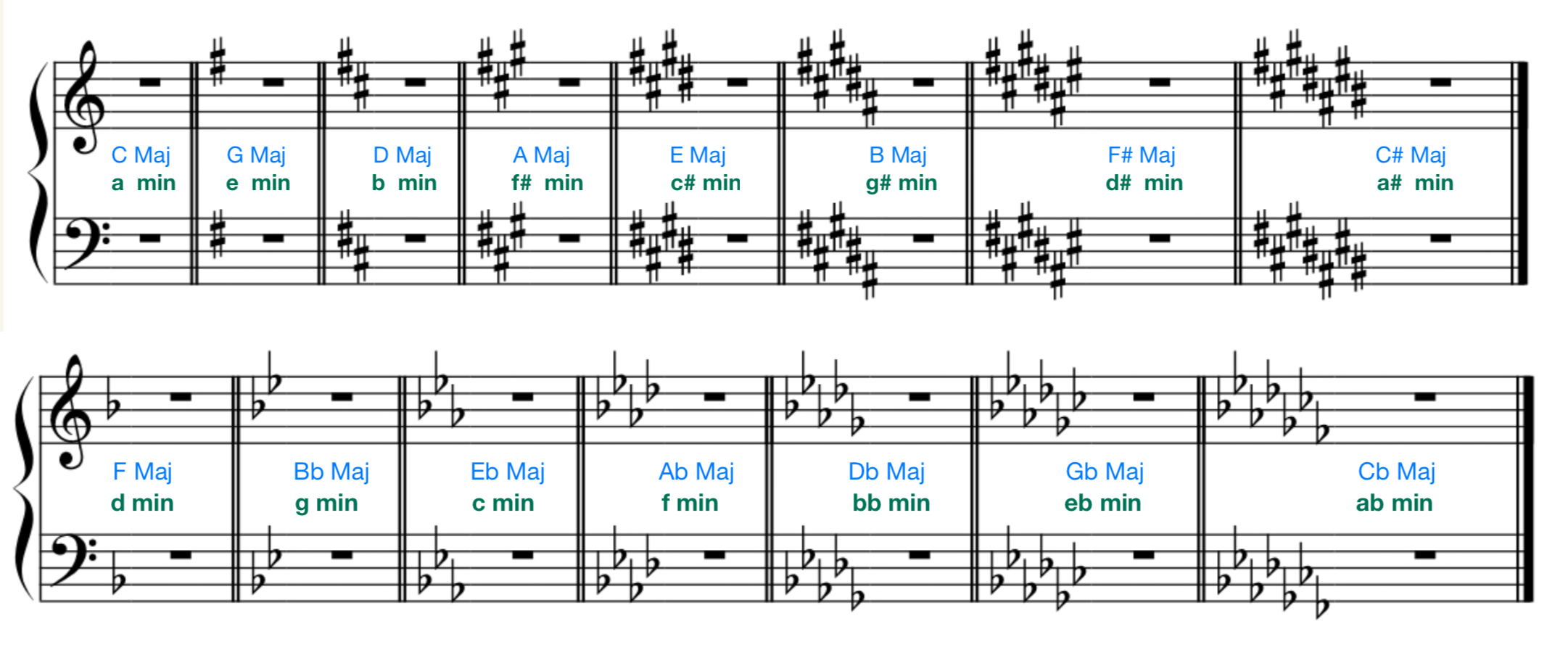

2.2: Relative Keys: Determining Relative Minor Key and Notating Key Signatures

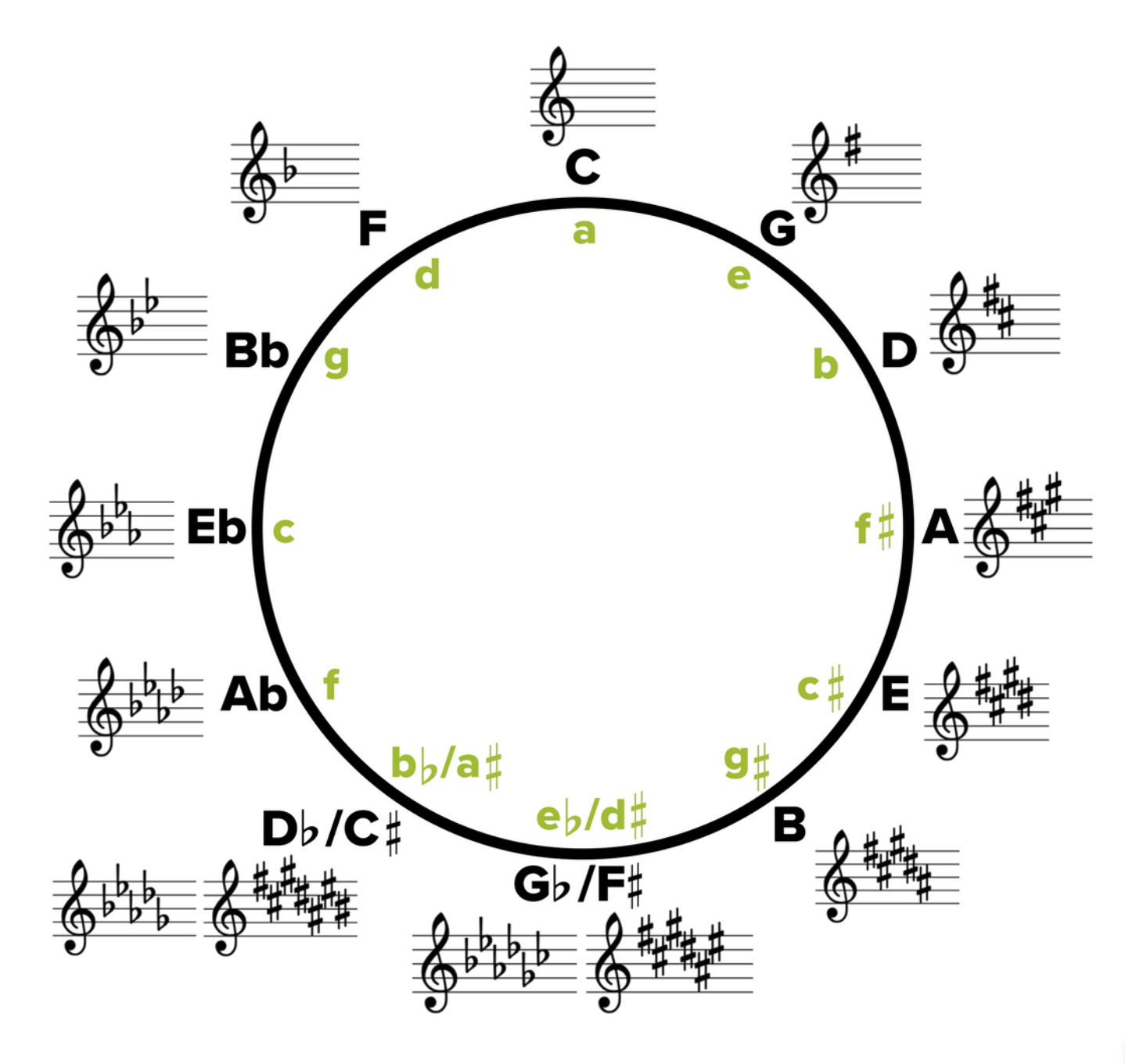

Relative keys are musical keys that share the same key signature, meaning they have the same pitches, but have a different tonic, or root pitch. For example, the key of C major and the key of a minor are relative keys, because they have the same pitches but their tonic pitches are different.

Relative keys are related by a distance of a minor third. The tonic of the major key is a minor third above the tonic of the relative minor key. For example, the tonic of D major is a relative third above the tonic of b minor. Therefore, C major and a minor have the same key signature.

2.3: Key Relationships: Parallel, Closely Related, and Distantly Related Keys

Parallel keys are musical keys that have the same tonic, or root pitch, but are written in different modes. For example, the key of C major and the key of C minor are parallel keys, because they both have C as their tonic pitch.

Here are the parallel keys D Major and d minor:

Closely related keys are musical keys that are closely related harmonically, meaning that they share many of the same pitches and chord progressions. These keys are often used in music to create smooth transitions between different sections of a piece. If keys are next to each other on the circle of fifths, they are considered to be closely related.

Distantly related keys are musical keys that are not closely related harmonically, meaning that they do not share many of the same chords and progressions. These keys are often used in music to create contrast and dissonance, and can be used to create a sense of tension and resolution in a piece.

2.4: Other Scales: Chromatic, Whole-Tone, and Pentatonic

Chromatic Scales

The chromatic scale is a musical scale with 12 pitches, each a semitone (or a half step) apart from its neighbors. The chromatic scale can be used to play any piece of music in any key, by starting on the desired tonic (root) pitch and using the appropriate pitches from the chromatic scale.

Usually, when you notate an ascending chromatic scale (the chromatic scale going up), you will use sharps as the accidentals, and when you notate a descending chromatic scale (the chromatic scale going down) you use flats.

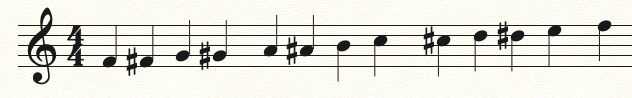

Here is what an ascending chromatic scale looks like:

Whole Tone Scales

The next unique scale is the whole-tone scale. The whole tone scale is a musical scale in which each note is separated from its neighbors by a whole step (a distance of two semitones). This scale consists of six notes, and is typically notated using the following scale degree notation: 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6.

You can identify the whole-tone scale by eye 👀 because it only has 6 different scale degrees, versus 7 in a major or minor scale. Remember that the last note in the examples are the resolution of the scale (the tonic), so it repeats the original pitch of the scale. If we include the tonic again, all major and minor scales have 8 notes total, and the whole-note scale would have 7.

Pentatonic Scales

There are two types of pentatonic scales: the minor pentatonic scale and the major pentatonic scale.

The minor pentatonic scale is made up of the 1st, 3rd, 4th, 5th, and 7th degrees of a natural minor scale. For example, the A minor pentatonic scale consists of the following notes: A C D E G

The major pentatonic scale is made up of the 1st, 2nd, 3rd, 5th, and 6th degrees of a major scale. For example, the C major pentatonic scale consists of the following notes: D E F# A B

Fun fact! You can take the minor pentatonic scale, add one note to it (between the 3rd and 4th notes of the above MINOR example, add an Eb/D#) and you suddenly have the blues scale.

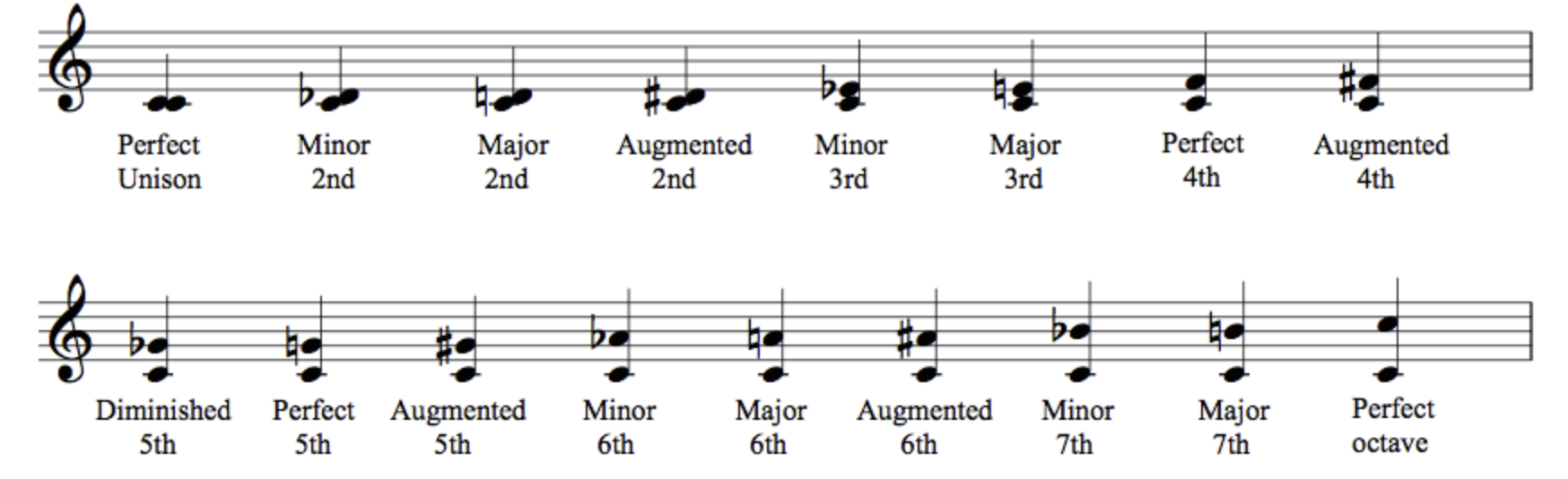

2.5: Interval Size and Quality

An interval in music refers to the distance in pitch between two notes. Intervals can also be classified as being either harmonic or melodic. Harmonic intervals are those that are played simultaneously, while melodic intervals are played one after the other. In music theory, the study of intervals is an important part of understanding how music works and how to create melodies, chords, and harmonies.

Intervals can also be described in terms of their quality, which refers to the type of interval (major, minor, etc.) and their size, which refers to the number of pitch classes they span.

An easy way to remember whether an interval is minor, major, perfect, etc. is to think about a major scale. A major scale has all major intervals, (e.g. M2, M3, M6, etc.) except for the 4th, 5th, and the octave, which are considered perfect intervals. For example, a C to an E is considered a major 3rd, but a C to a G is a perfect 5th. You usually don't say "perfect octave" or "perfect 8th" -- just "octave" is good enough.

Once you know the major intervals, a minor interval is one half step less than a major interval. So, if C to E is a major 3rd, then C to Eb is a minor 3rd. These don't necessarily correspond to the minor scale. C to Db is a minor 2nd, but C#/Db is not in the c minor sale. You cannot turn perfect intervals into minor intervals. For example, you will not have a minor 5th or a minor 8th.

When you augment an interval, you add one half step to the major interval. For example, C to E# is an augmented 3rd. When you learn about voice leading in Unit 4, you will most likely talk about augmented 2nds and augmented 4ths as things to avoid in part-writing. A diminished interval takes a minor interval and takes away one half step. For example, a C to a E double flat would be a diminished 3rd. The most common diminished chords you will run into are diminished 7ths (for example, C to B double flat) and diminished 5ths (C to Gb).

Here are all of the intervals:

The intervals that create tension or instability are called dissonant intervals, and the intervals that create a sense of resolution or stability are called consonant intervals. Using dissonance is not always bad. In fact, good music usually requires you to write some dissonance to build tension before you resolve to consonant intervals and chords.

Consonant intervals are the octave, perfect 5th, and major and minor thirds and 6ths. Dissonant intervals are the major and minor 2nds, the tritone, major and minor sevenths, and any augmented or diminished intervals. What about the perfect 4th? In short, it depends. In some contexts, the perfect 4th is very stable. However, in other contexts, the perfect 4th wants to resolve to the perfect 5th, so it is considered unstable and dissonant.

2.6: Interval Inversion and Compound Intervals

Interval inversion is the process of taking an interval (the distance between two pitches) and finding its "opposite." For example, the inversion of a perfect fifth (an interval consisting of seven half steps) is a perfect fourth (an interval consisting of five half steps). The inversion of a major third (an interval consisting of four half steps) is a minor sixth (an interval consisting of eight half steps).

Compound intervals are intervals that span more than one octave. In music, we sometimes have very big intervals, but saying that two notes are a 24th apart is not as meaningful as saying that two notes are 3 octaves and a 3rd apart. The 3rd creates the unique sound of the interval – moving a note up or down an octave doesn’t really matter too much in terms of interpreting consonance, dissonance, and interval quality.

2.7: Transposing Instruments

Transposing instruments are instruments that are notated in a different key than they sound. This means that when music is written for a transposing instrument, the written notes are different from the actual pitches that are played.

For example, a saxophone is a transposing instrument because the music written for it is notated in the key of C, but the pitches that are actually played are transposed down a certain number of half steps (a measure of the distance between two pitches). Since the saxophone is in Bb, the notes that you hear are two half steps below the notes you read on the score.

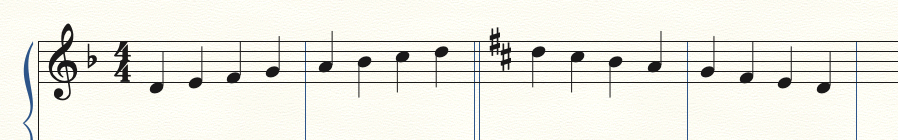

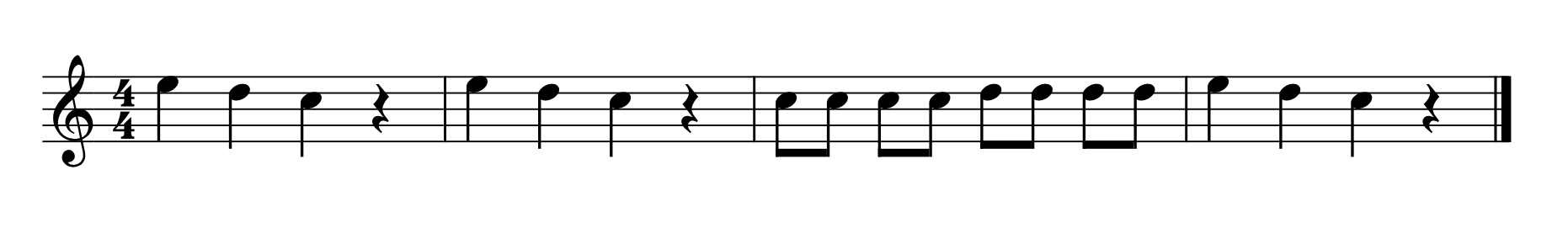

So, if you want to notate this melody for saxophone:

You would have to actually write each note up a Major 2nd. The red notes are concert pitch, and the black notes are the notated melody:

2.8: Timbre

In music, timbre (also known as "tone color" or "tone quality") refers to the distinctive sound of a musical instrument or voice. It is what allows us to distinguish between different instruments or voices, even when they are playing the same pitch.

Timbre is an important aspect of orchestration, which is the art of arranging and scoring music for an orchestra or other ensemble. When orchestrating a piece of music, a composer or arranger must consider the timbre of each instrument and how it will contribute to the overall sound of the piece.

2.9: Melodic Features

Melody is the intersection of pitch and rhythm. A melody is created when a succession of pitches are played over a certain amount of time, expressing a musical statement. Often they are derived from scales and modes, and are organized into patterns that create musical phrasing and motives.

- Rising: A melody that moves upward in pitch.

- Falling: A melody that moves downward in pitch.

- Arching: A melody that begins and ends on a high or low pitch, with the pitches in the middle of the melody rising or falling.

- Leaping: A melody that makes large jumps in pitch, either upward or downward. Melodies often have certain technical features, including contour, conjunct and disjunct, register, and range.

Melodic contour refers to the shape or direction of a melody. It describes the overall movement of the pitch of the notes in a melody, and can be thought of as the "ups and downs" of the melody.

Some common examples include:

- Stepwise: A melody that moves in small steps, either upward or downward

-

- Rising: A melody that moves upward in pitch.- Falling: A melody that moves downward in pitch.

-

- Leaping: A melody that makes large jumps in pitch, either upward or downward.

The stepwise movement of pitches in a melody is known as conjunct motion. This creates a sense of continuity and flow in the melody.If we’re only moving in steps, though, we lose interest in the piece. We want to add a few skips and leaps, too. For this, we have disjunct motion.

2.10: Melodic Transposition

Melodic transposition is simply moving a melody or melodic segment to a new pitch level while maintaining the same intervals and rhythms within that melody. Melodic transposition is the process of shifting a melody to a different pitch level while maintaining its original intervallic structure. This means that the distances between the notes in the melody remain the same, but the starting pitch and the overall pitch range of the melody are changed.

2.11: Texture and Texture Types

When we talk about texture, we refer to how many instruments or voices are performing concurrently and how their collective timbres, density, and pitch range all align.

The main types of texture in music are monophony, homophony, and polyphony.

- Monophony: one sound played or sung simultaneously.

- Homophony: one note or voice plays at the same time, but the harmonies are filled out for each change of note

- Polyphony: has multiple melodic lines occurring simultaneously.

Counterpoint

Generally speaking, a counterpoint is a melodic or rhythmic line that is harmonically interdependent with a main melody, but provides a distinct and independent voice. Counterpoint is an important element of many forms of Western classical music, such as fugues and choral music, and it has also been used in many other musical traditions around the world.

In Western classical music, counterpoint is typically based on the principles of tonality, in which certain pitches are considered more stable or "tonic" than others. This creates a sense of tension and resolution as different voices move against or with each other in relation to the tonic.

General Counterpoint Rules

- The beginning and the end of the counterpoint have to be perfect consonance (i.e. perfect octaves or perfect fifths). If you are approaching the tonic from below, you should raise the leading tone

- You should prefer contrary motion (one voice going down and one voice going up, or vice versa) or oblique motion (one voice staying the same and one voice going up or down). Perfect consonances should always be approached by contrary or oblique motion

- You should try not to go beyond an interval of a 10th between the two voices

- You should always avoid the tritone

- The line opposing the cantus firmus (the bass line) should have a “high point,” preferably on a strong beat

- If you have a skip in one direction, you should follow it by a step in the opposite direction.

2.12: Texture Devices

There are three special forms of counterpoint that create unique textures: canonical music. imitation counterpoint, and countermelodies.

A canon is a type of musical composition in which a melody is imitated by one or more voices in a staggered or overlapping fashion. Canons are often characterized by their strict, formal structure and their use of repetition and imitation as compositional devices.

Imitation counterpoint is a type of counterpoint in which one voice imitates the melody of another voice, either exactly or with some variations. Imitation is a common technique in counterpoint and is used to create a sense of unity and coherence among the voices.

Finally, a countermelody is a secondary melody that is played or sung at the same time as the main melody in a piece of music. It is typically played by a different voice or instrument and serves to add interest, variety, and harmonic complexity to the music.

2.13: Rhythmic Devices

When talking about rhythm, there are some terms that can help us describe specific features in music.

- Syncopation is a rhythmic technique that involves shifting the accent of the music from its expected or normal accent pattern to a weak or off-beat rhythm.

- Polyrhythms are rhythms in which the voices subdivide the beat in a way that doesn’t line up.

- During a hemiola, the time signature stays as originally written, but the feeling is as if the meter has shifted. For example, in a 2/4 meter, if there are suddenly three notes every measure, the feeling is as if the meter has changed to 3/4 or 3/8 in a different tempo, but when reading the music, the notes are still aligned in a 2/4 bar.

- An agogic accent is a note that naturally receives more emphasis due to its extended duration, or accents that are placed in an unnatural flow of the established meter.

- A fermata is a symbol placed over a note or rest that indicates that it is to be held longer than its normal duration.

© 2024 Fiveable Inc. All rights reserved.