<< Hide Menu

Mickey Hansen

Mickey Hansen

Just like there are various textures of clothes, hair, or food, there are also different textures in music. When we talk about texture, we refer to how many instruments or voices are performing concurrently and how their collective timbres, density, and pitch range all align.

The main types of texture in music are monophony, homophony, and polyphony.

Breaking down the Greek 🇬🇷 base on the words, mono means: one. Phony means: sound.

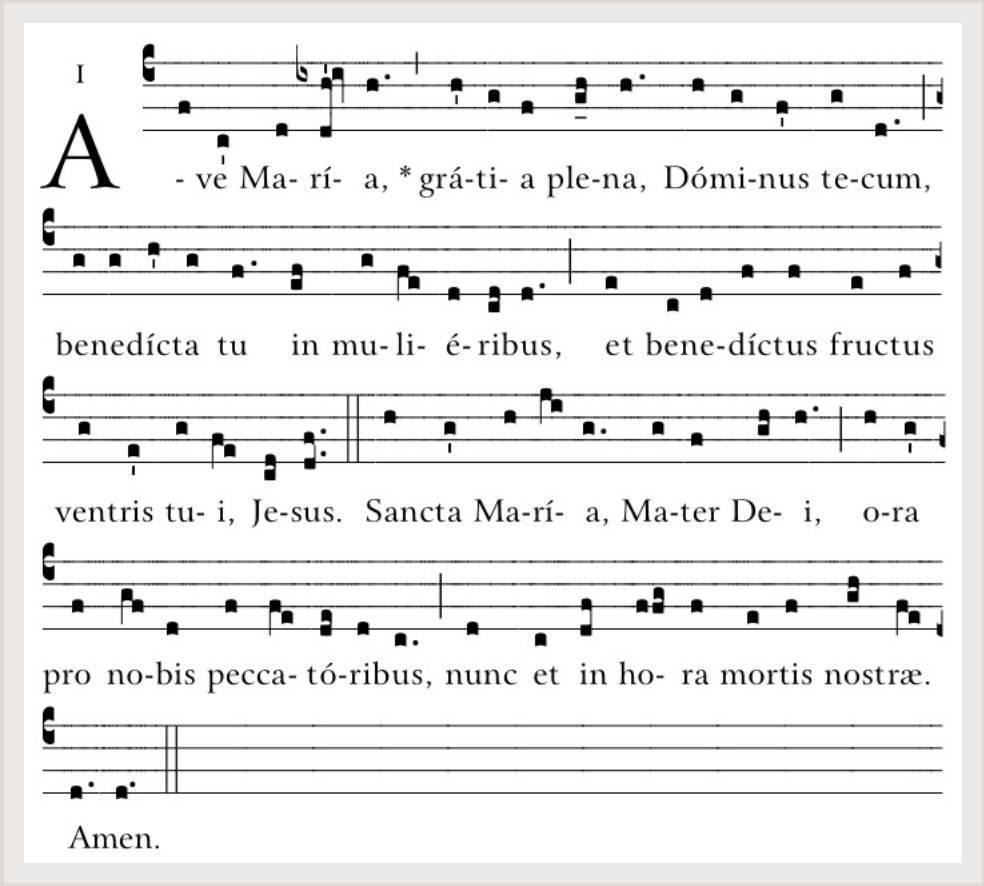

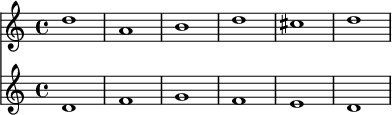

Monophony: one sound played or sung simultaneously. An example of monophony is plainchant (also often referred to as Gregorian chant). Here is an example of plainchant in its original written form:

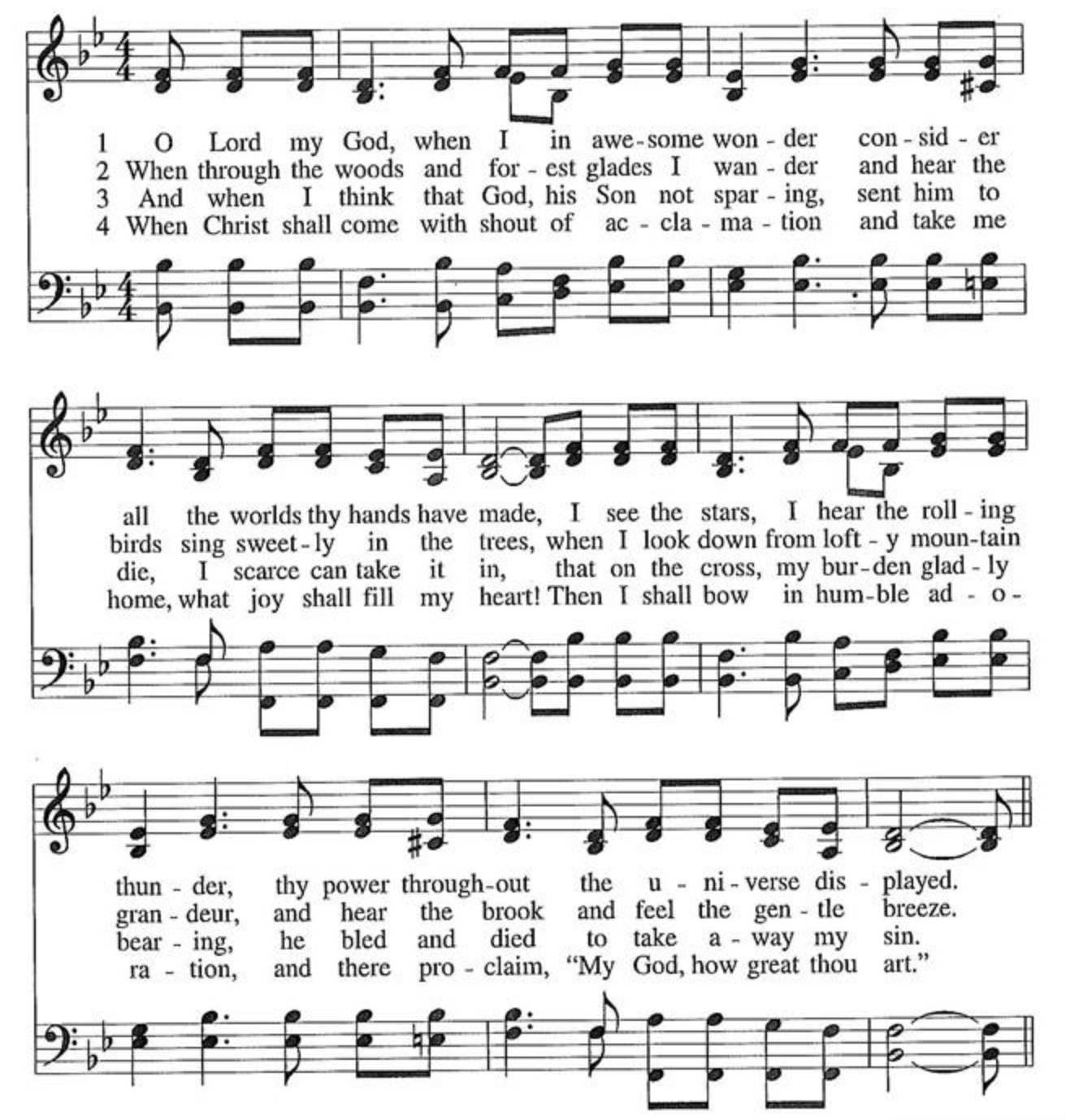

Similarly to monophony, homophony, Greek for "same sounds", has one note or voice playing at the same time, but the harmonies are filled out for each change of note. As example of this would be a church hymn, such as this hymn, "O Great Thou Art":

While monophony and homophony have only one musical line going at one time, polyphony, or "many voices" has multiple melodic lines occurring simultaneously.

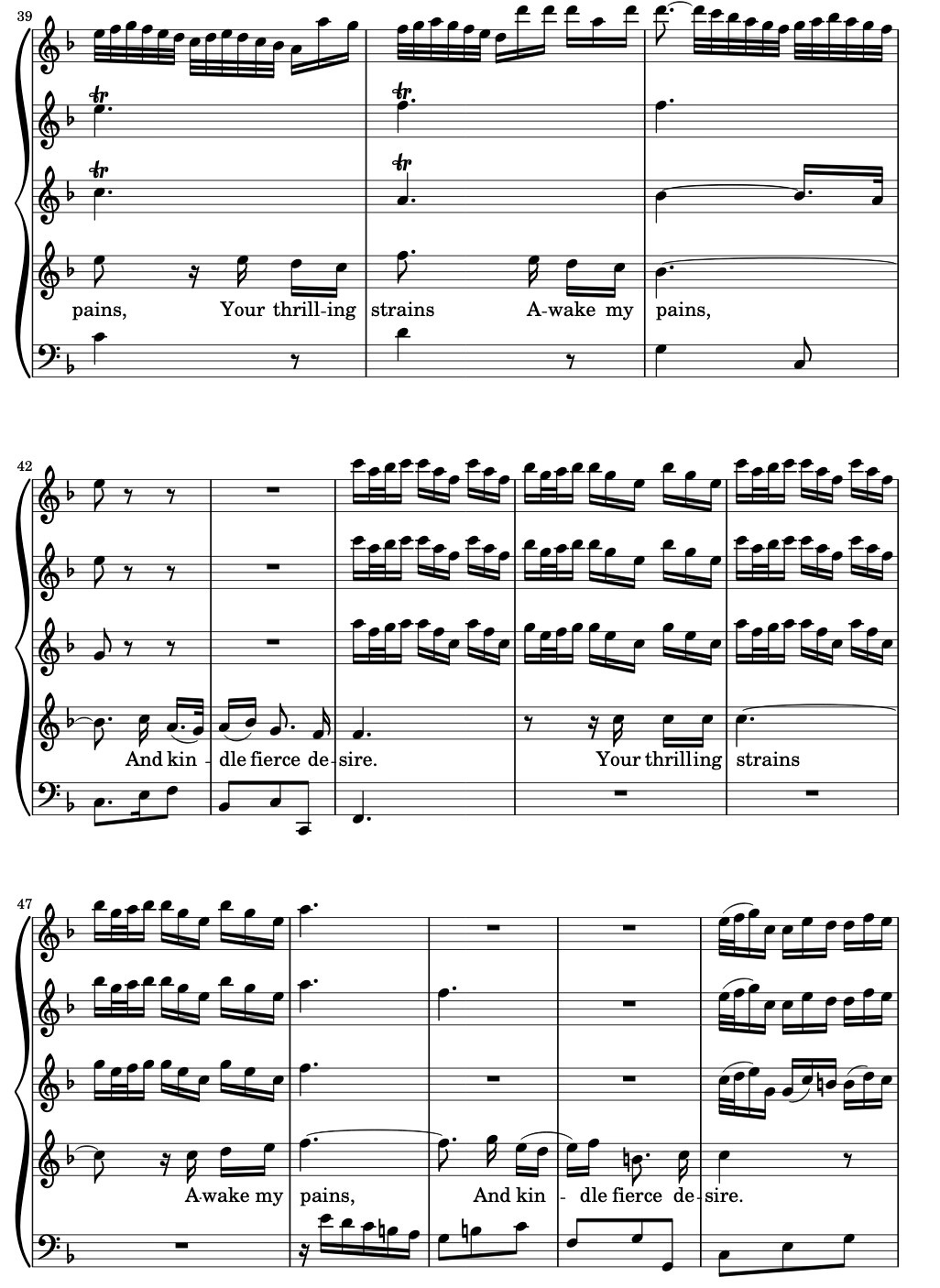

Here is an excerpt from Händel's aria, "Ye Verdant Plains"

Image from Gregorian Chant Hymns

Similarly to monophony, homophony, Greek for "same sounds", has one note or voice playing at the same time, but the harmonies are filled out for each change of note. As example of this would be a church hymn, such as this hymn, "O Great Thou Art":

Image from Presbyterian Hymnal

While monophony and homophony have only one musical line going at one time, polyphony, or "many voices" has multiple melodic lines occurring simultaneously.

Here is an excerpt from Händel's aria, "Ye Verdant Plains"

Image from IMSLP

Counterpoint

We saw that music started with mostly monophonic tunes, and then slowly evolved into primarily homophonic and then polyphonic pieces. In Western musical history, this evolution necessitated that certain musical rules were created and followed so as to make sure that music sounded good and pleasing to the ears. This evolution can be seen through contrapuntal music. Counterpoint was developed in the Baroque era.

Generally speaking, a counterpoint is a melodic or rhythmic line that is harmonically interdependent with a main melody, but provides a distinct and independent voice. Counterpoint is an important element of many forms of Western classical music, such as fugues and choral music, and it has also been used in many other musical traditions around the world.

In Western classical music, counterpoint is typically based on the principles of tonality, in which certain pitches are considered more stable or "tonic" than others. This creates a sense of tension and resolution as different voices move against or with each other in relation to the tonic.

If something is considered contrapuntal, it refers to the practice of composing polyphonic music, often using historical conventions, and the texture that results. J.S. Bach is most famous for his writing in counterpoint. His many children, who also became composers, used counterpoint too!

There are several species of counterpoint that correspond to the historical development of musical rules. At first, musical rules were very strict, and there was very little leeway for creativity. As time went on, composers started breaking these rules, and the guidelines became more relaxed. This process of breaking rules to develop new musical styles happens in musical history all the time, even after counterpoint was developed!

General Counterpoint Rules

There are some rules that apply to counterpoint regardless of which species of counterpoint we are using. In general, contrapuntal music wants to achieve the following:

- Consistency: The voices should be consistent in terms of their rhythms, melodies, and harmonies. This means that each voice should have a clear and distinct character, and the voices should work together to create a coherent musical texture.

- Balance: The voices should be balanced in terms of their relative importance and independence. This means that no one voice should dominate the others, and each voice should be able to stand on its own as a melodic or rhythmic line.

- Contrast: The voices should be varied and interesting, and should provide a sense of contrast and variety within the overall texture. This can be achieved through the use of different melodies, rhythms, and harmonies.

- Progression: The voices should move forward and develop over the course of the piece, avoiding static or repetitive patterns. This can be achieved through the use of melodic and harmonic motion, as well as through the use of varied rhythms and textures.

- Clarity: The voices should be clearly audible and distinct from one another, and the overall structure of the piece should be easy to follow. This can be achieved through the use of good voice leading, which refers to the way in which the voices move from one pitch to another.

There are also some more specific rules that all species of counterpoint have to follow.

- The beginning and the end of the counterpoint have to be perfect consonance (i.e. perfect octaves or perfect fifths). If you are approaching the tonic from below, you should raise the leading tone

- You should prefer contrary motion (one voice going down and one voice going up, or vice versa) or oblique motion (one voice staying the same and one voice going up or down). Perfect consonances should always be approached by contrary or oblique motion

- You should try not to go beyond an interval of a 10th between the two voices

- You should always avoid the tritone

- The line opposing the cantus firmus (the bass line) should have a “high point,” preferably on a strong beat

- If you have a skip in one direction, you should follow it by a step in the opposite direction.

Wow! These are a lot of rules! Don’t sweat it too much – the rules will get easier to follow as you keep practicing writing counterpoint. You will not have to write counterpoint from scratch in the AP exam, but these rules form the basis for the voice leading rules that you will have to know by heart.

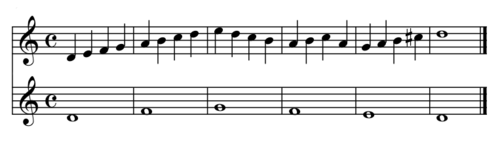

Let’s look at an example:

Image via Wikipedia

Notice how the bass line is its own independent musical line, and the top line is also independent. However, they are combined in such a way that they sound good together. This is a very simple example of contrapuntal music, but there can be even more complex melodies. A fugue is also considered a form of counterpoint.

Contrapuntal Species

But wait… there are more rules! Counterpoint is divided up into species, each of which has its own rules and stylistic guidelines (on top of the rules that we already mentioned).

First species counterpoint is the simplest and most restrictive form of counterpoint, as it allows for very little melodic or rhythmic variation. In first species counterpoint, all of the notes sound together on strong beats, and so you only use whole notes.

There are several rules that are typically followed in first species counterpoint, including:

- The cantus firmus must be in a stable key, and the accompanying voices must stay within the boundaries of that key.

- The cantus firmus should be in a consistent rhythm, and the accompanying voices should match that rhythm.

- The accompanying voices should not move too far away from the cantus firmus, generally staying within a range of a fifth or sixth above or below it.

- No more than one voice should move by leaps (intervals larger than a second), and these leaps should be avoided when possible.

- The voices should not cross or overlap.

Here’s an example of first species counterpoint

Image via Wikipedia

In second species counterpoint, we follow many of the same rules as first species counterpoint, but we now have two notes in the top line for every one note in the cantus firmus. We should only put consonances on the strong beats, and we can put dissonances on the weak beats. However, we should be careful of parallel octaves and parallel fifths, meaning that two successive intervals, or the downbeats of two successive measures, should not both be fifths or both be octaves.

Third species counterpoint is similar to second species counterpoint, but now there are 4 on 1 melodies. In third species counterpoint, we start introducing melodic embellishments and non-chord tones. We will learn about these in Unit 6!

Other Musical Textures

Outside of the 18th century composition style, another textural device, called call and response, refers to a soloist who is repeated by a chorus. The soloist is the "caller" and the chorus responds.

Many gospel songs rely heavily on the format of call and response, as a genre development of field songs from southern plantations in 17th to 19th century United States.

We also see “call and response” formats in instrumental music. For example, Bach’s inventions frequently employ call and response melodies. Listen to the first invention and see if you can identify this texture.

There are a few more terms we should know that refer to the texture of music.

Have you ever sung the song "Row, Row, Row Your Boat" in a group and had someone else start a bit after you? There can be several groups of singers singing the same song at different times.

This structure refers to a canon when one part is sung or played, and the same musical part is layered on top, but displaced by time. A musical composition that has features of a canon can be considered canonic.

🦜 Polly wants a progress tracker: If you are sitting around a campfire and someone is playing guitar, and the rest of the group is singing the same song together, which kind of texture would this be?

© 2024 Fiveable Inc. All rights reserved.