<< Hide Menu

Cesar Torruella

Cesar Torruella

Last section, we talked about cadential 6/4 chords, which are I 6/4 chords that precede a root position dominant triad, usually at a cadence. Even though this I 6/4 chord has tonic harmonies, it actually has a dominant function, because its bass is the dominant scale degree, and its upper voices quickly resolve to the dominant. In other words, even though the I 6/4 chord is technically a chord, it is not used to build a harmony. Rather, it is used as an embellishment to the dominant harmony that follows it.

The reason why 6/4 chords are usually used as embellishments is because they are generally weak chords. If you have a keyboard or piano near you, consider playing a I chord in C Major. Now, invert the chord so that you’re still playing a I chord, but it is in second inversion, i.e. a I 6/4 chord. You will probably notice that the tonic quality of the C Major chord is far less prominent. Similarly, a V 6/4 chord doesn’t really sound like a dominant chord, and a IV 6/4 chord doesn’t really sound like a subdominant chord.

Aside from cadential 6/4 chords, we usually see 6/4 chords in three other contexts: neighboring or pedal 6/4 chords, passing 6/4 chords, and arpeggiated 6/4 chords. We’ll go through each of these types of 6/4 chords one by one, and learn what they are and how to write them using proper voice leading.

Neighboring or Pedal 6/4 Chords

The pedal 6/4 chord, also called the neighboring 6/4 chord, occurs when the third and fifth of a root-position triad are embellished by upper neighbor tones while the bass line stays the same.

For example, suppose that we are in Ab Major and we want to embellish two root position I chords using a pedal 6/4 chord. Since the bass must remain the same for all three chords, we have to choose a IV chord for our passing 6/4 chord. This is because the bass of the root position tonic triad in Ab Major is Ab, and the bass of the second inversion IV chord, the IV 6/4 chord, in Ab Major is also Ab.

Next, we write the chord progression such that the upper voices in the I chord move up to spell the IV 6/4 chord. In this case, the upper voices of the I chord would be C and Eb, and the upper voices of the pedal 6/4 chord would be Db and F.

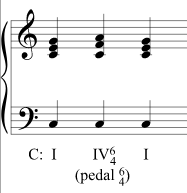

Here is an example of a pedal 6/4 chord in C Major:

Passing 6/4 Chords

In music, a passing tone is a musical note or chord that is played or sung briefly as a transition between two other notes or chords in a melody or harmony. It is typically used to create a sense of movement or tension and release in a piece of music. Passing tones can be diatonic or chromatic, meaning they come from within the key or scale being used, or they can come from outside of it.

A passing tone is a type of non-chord tone. As we have seen before, a non-chord tone is a musical note or tone that is played or sung in a melody or harmony that does not belong to the chord that is currently being played. Non-chord tones can be dissonant or dissonant-sounding and can be used to create tension and dissonance in a piece of music.

That being said, you can harmonize a non-chord tone without having the chord associated with the non-chord tone be a part of the chord progression. This sounds a little confusing – doesn’t a chord in a chord progression have to be part of the chord progression, by definition? Well, yes and no. When I say that the chord isn’t part of the chord progression, I mean that it doesn’t add any harmonic value to the piece. Let’s consider an example:

Say you are in the tonic section of a phrase, and you have a I chord followed by a I6 chord. What does the bass line look like? You will have the tonic followed by the mediant. If you want to add some melodic interest to the bass line, you might consider adding the supertonic in between the tonic and the submediant, so that you have a nice stepwise melody. You’ve just added a passing tone in the bass line.

But perhaps you want to go a little further than that, and add notes in the other voices that blend well with this melody in the bass line. Of course, you could insert a ii chord or a vii6 chord in between these notes, but the ii chord has a strong predominant function, and the vii6 chord has a really strong dominant function. It would sound pretty weird to go from a tonic chord to a predominant chord back to a tonic chord, and although vii6 chords can be used as pedal tones between two I chords, as we’ve seen earlier, you’re not looking for such a strong chord. You’re looking for a weak chord that clearly doesn’t add to the harmonic progression. Your other option is to add a V 6/4 chord between the tonic chords. This is a passing 6/4 chord.

Any type of 6/4 chords are weak, meaning that they don’t really sound like the chord defined by their root. In other words, inserting a V 6/4 chord in between the two tonic chords won’t really sound like a tonic-dominant-tonic progression. It will just sound like a tonic chord, some other notes, and then another tonic chord. The benefit to this approach is that you will keep a strong tonic harmony while still adding melodic interest to the piece.

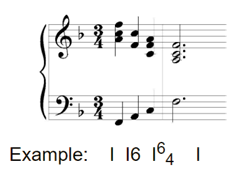

Let’s see what this looks like in practice:

Image via https://academic.udayton.edu/PhillipMagnuson/soundpatterns/diatonicII/secondinv.html

Here, we are in Eb Major, and we see a I-V 6/4-I6 progression in the first three chords of the passage. This gives us an ascending stepwise melody (Eb-F-G) in the bass line.

Voice Leading with Passing 6/4 Chords

Let’s talk about voice leading with passing 6/4 chords. Firstly, the 6/4 chord should almost always appear on a weak beat in the measure. In this case, where we are in 4/4 time and we are using quarter notes, the V 6/4 chord occurs on the second beat, which is weaker than the first and third beats, where the tonic chords are written.

Second, the upper voices should move stepwise when voice leading into and out of the passing 6/4 chord. Notice how in this example, the soprano voice moves down stepwise, mirroring the bass line. If you can achieve this while maintaining our other voice leading rules, then you will create a beautiful voice exchange between the soprano and bass lines, and your music will sound really nice.

Arpeggiated 6/4 Chords

Finally, let’s talk about arpeggiated 6/4 chords. An arpeggio is a type of broken chord where the notes of a chord are played in a sequence. For example, an ascending C Major arpeggio will be C-E-G, and a descending C Major arpeggio would be G-E-C. You can invert arpeggios just like you do with chords. However, arpeggios are usually ascending or descending. For example, you wouldn’t play E-G-C such that E is a lower note than G but C is lower than E and G.

We can use 6/4 chords to harmonize arpeggios in the bass line. For example, you might write a I chord followed by a I6 chord, so the bass line goes from the tonic to the mediant. To complete the arpeggio, you might write a I 6/4 chord, so the bass line has a tonic-mediant-dominant melody. It is good practice to sustain the upper voices when writing arpeggiated 6/4 chords – meaning that the upper voices should stay the same and not jump around. We will usually write the 6/4 chord on a weak beat.

Here is an example:

Sometimes, we will just have a I chord followed by a I 6/4 chord. This is quite common in waltzes, which are pieces written in 3/4 time. Waltzes usually have a strong downbeat and two lighter upbeats, so we might have a I chord on the downbeat followed by two I 6/4 chords on the upbeats.

Note that while arpeggiated 6/4 chords don’t have to be written with the I chord, they usually are. It is also common to see arpeggiated V 6/4 chords. However, it is rare to see these written on other diatonic chords, although you might still see them occasionally.

Other Voice Leading Rules There are some final voice leading rules to sum up this section. Good news: after this you’re almost done with voice leading. You’ll learn some new melodic techniques and new ways to interpret chords, but there will be less rules in the coming units. Hang in there – you got this!

First, you should note that there are some unacceptable chord progressions that you should avoid. They are:

- V-IV

- V-ii

- Ii-iii

- IV-iii

- ii-I

- V-vi6

- and iii-viio

If you’re wondering why this is the case, consider the T-PD-D-T phrase we discussed earlier. All of these chord progressions are moving backwards in this progression, resulting in poor voice leading.

Finally, there are some chords that you should just avoid completely. They are root position viio chords, vi6 chords, and iii6 chords. You might see the latter two when you learn about modulation in Unit 7. However, they are rare and you should try not to use them when writing your own chord progressions. Also, if you are realizing a figured bass and you come across these chords, make sure to check your work! They usually won’t appear on this section of the AP Exam.

© 2024 Fiveable Inc. All rights reserved.