<< Hide Menu

Sumi Vora

Sumi Vora

A phrase is like a musical sentence. A phrase in music is a unit of musical structure that typically consists of a group of notes and rhythms that are played or sung together. A phrase usually has a clear beginning and ending, and is often characterized by a sense of completeness or satisfying resolution.

Phrases can be of varying lengths and can be made up of smaller units such as motives or figures. In a melody, a phrase is often distinguished by a change in rhythm, melody, harmony, or timbre. In harmony, a phrase often corresponds to a harmonic progression, and in rhythm, a phrase corresponds to a rhythmic pattern. Phrases are used by composers to structure music, to create contrast and variety, and to create a sense of development and movement in a piece.

Like a sentence in language, a phrase in music conveys a musical thought or idea, and has a beginning and ending. Additionally, phrases can be combined to create larger structures, like movements or sections of a piece, just as sentences can be combined to create a larger piece of writing.

For much of this course, we have been talking about what happens inside of phrases. The tonic-predominant-dominant-tonic chord progression often all happens within one phrase, as the stability-tension-resolution structure of this phrase makes it a complete musical idea. In classical music, phrases always end with some type of cadence. However, this doesn’t mean that phrases always end conclusively. We’ve talked about how we can use half cadences or deceptive cadences at the end of phrases in order to delay resolution or only partially resolve a musical idea.

In the Baroque and Classical eras, musical phrasing took on a far more structured form – phrases were generally approximately the same length throughout a piece, and phrases were structured in such a way that the ending of a phrase was distinct from the beginning of the next phrase. As music became freer and more expressive in the Romantic and Modern periods, phrase structure also became more ambiguous, and phrases began “running into each other.”

🦜 Polly wants a progress tracker: Listen to these two pieces of music from different periods and see if you can identify the phrases in each piece:

- Mozart Piano Sonata No 12 in F Major, K 332, 1st Movement: Allegro

- Debussy Arabesque No 1 in E Major Which piece has a more clear phrase structure? Which piece has more conclusive cadences at the end of phrases?

Analyzing Phrase Relationships

How do phrases fit together to create a complete piece of music?

We can characterize the relationship between two subsequent phrases based on how similar they are to each other. If we have two phrases that sound pretty much the same, we will denote each phrase by the letter a, so we have an a a phrase relationship.

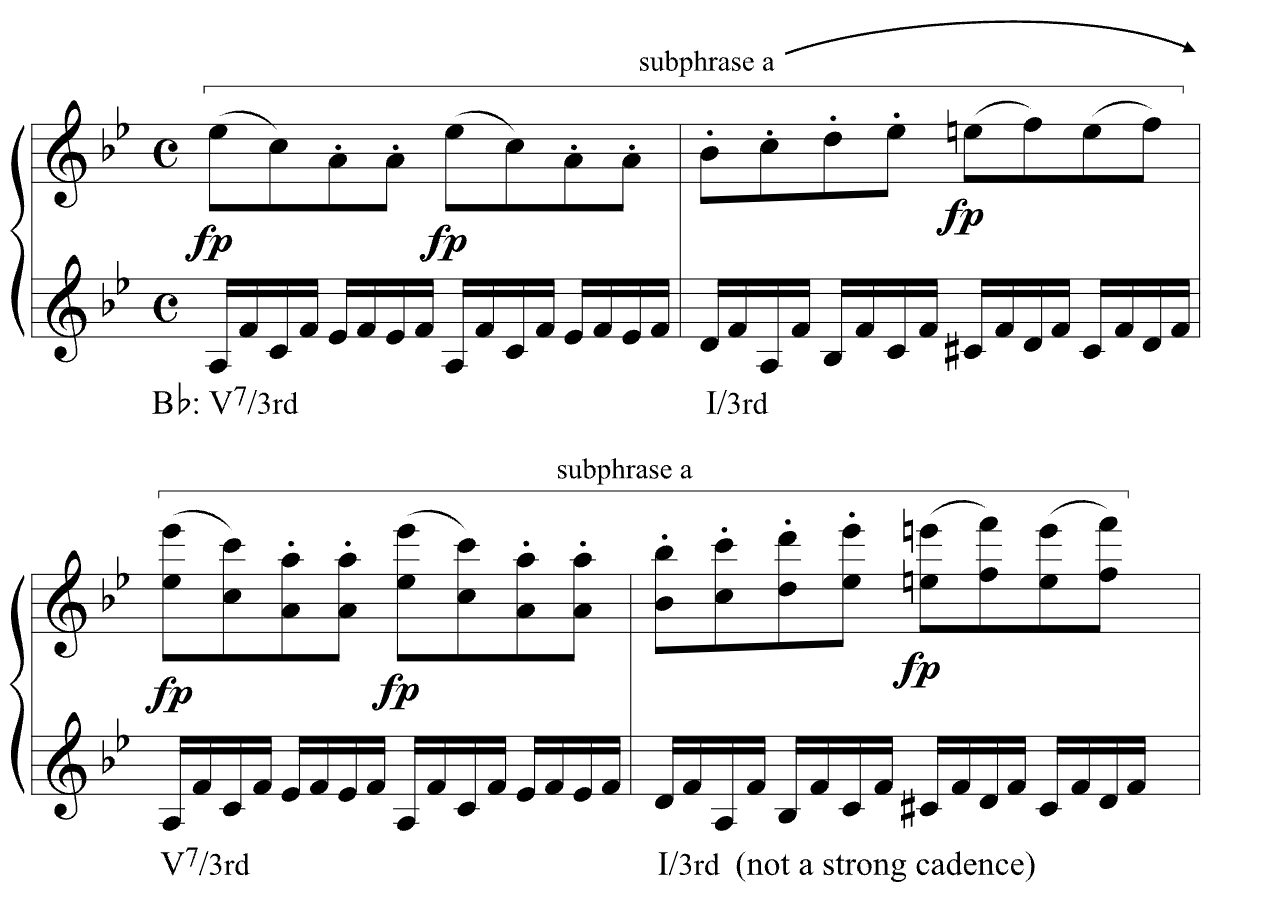

Here’s an excerpt of the first movement of Mozart’s Sonata No 12 in Bb Major, K 331. Notice how the two subsequent phrases (denoted as subphrases in the analysis) are pretty much exactly the same: the second phrase just doubles the soprano voice by an octave.

Image via Open Music Theory

If the basic structure, melodic, and harmonic ideas in subsequent phrases are repeated, but they are varied noticeably between phrases, then we denote it as an a a’ phrase relationship (read “a a prime phrase relationship”)

There are many ways to vary a phrase while still maintaining the same basic harmonic structure and melody. The most common way is to add or subtract non-chord tones, decorations, and melodic elements. If the composer wants to add drama and tension between one phrase to the next, then they will add more non chord tones. Conversely, if they want to reduce the tension and excitement, they will use less non-chord tones in the a’ phrase.

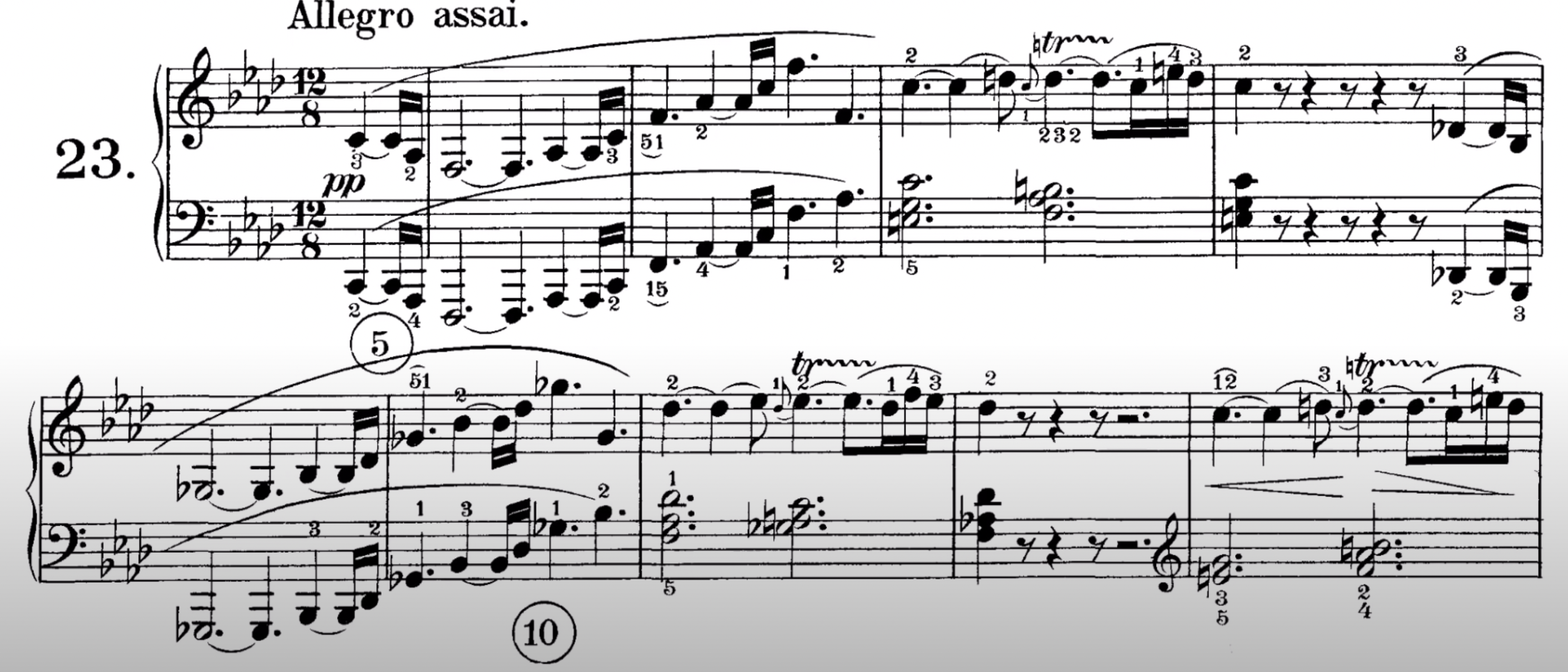

Another way to construct a a’ phrase structure is to transpose the phrase into another key, either diatonically or chromatically. Here is an example from Beethoven’s Appassionata Sonata:

Finally, a b phrase relationships consists of contrasting phrases. There might be harmonic contrast, but the phrases more importantly have melodic contrast. Here is an example from Beethoven’s Sonatina in F, Anh. 5 No. 2, II. Rondo.

Image via Open Music Theory

This is also an example of a phrase chain, in which two adjacent phrases have contrasting melodies, and the chain ends with a half cadence.

Periods

You might have noticed by now that it is very convenient to group phrases into 2s and 4s in order to analyze their relationships. Groups of two phrases have a special name in music theory – they are called periods.

Specifically, a period of phrases is a musical structure that consists of two phrases, usually of similar length and structure, that are balanced and complete each other. The first phrase, the antecedent phrase, sets up a musical idea or question and the second phrase, the consequent phrase, provides a resolution or answer to that idea or question. Together, the antecedent and consequent phrases form a complete musical thought or sentence.

In order for a group of phrases to be a period, the second phrase must end more conclusively than the first. For example, the first phrase may end in a deceptive cadence or a half cadence, and the second phrase might end in an imperfect authentic cadence, or, the first phrase might end in an imperfect authentic cadence and the second phrase might end in a perfect authentic cadence.

We can extend the idea of periods to bigger structure called Sonata Form, which is a large-scale musical form that is often used in sonatas, symphonies and other large-scale compositions in the classical era.

In the sonata form, the first phrase or period will be the Exposition, where the main themes or ideas will be presented, and the second phrase or period will be the Development, where the themes or ideas will be developed and transformed, and finally, the Recapitulation, where the themes will be presented again in the tonic key.

Types of Periods

However, let’s just stick with phrase periods for now. There are several types of periods in music: parallel, contrasting, modulating, asymmetrical, and double periods.

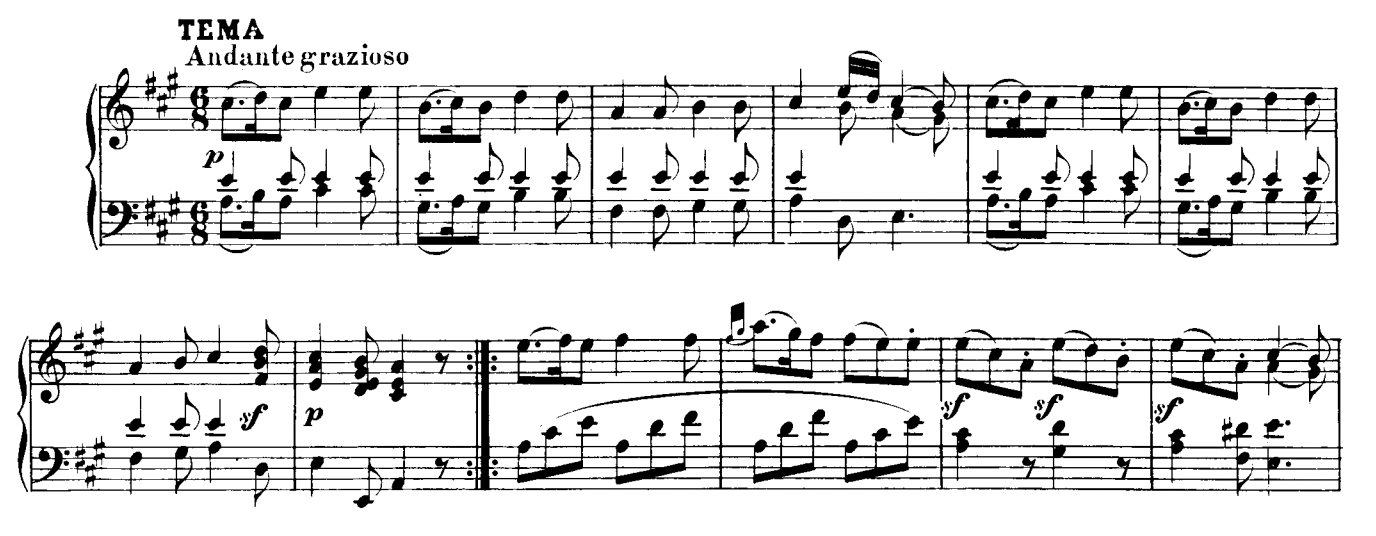

In parallel periods, the melodies of the antecedent and consequent begin similarly, although they might diverge at some point. A good example of a parallel period is the beginning of Mozart’s Sonata No 11 in A Major, K 331. Take a look at the first few bars:

In bars 1 through 4, we have the antecedent. It introduces a melody, and then ends on the first beat of the 5th bar in an imperfect authentic cadence (since the soprano is the third of the chord instead of the tonic). In bars 5-8, the melody is repeated, almost exactly, but this time, the phrase ends in a perfect authentic cadence.

Phrases that make up contrasting periods, on the other hand, will begin differently from one another (hence the name contrasting). Here is an example of a contrasting period:

Image via Dr. Christ

Notice here that the first phrase is shorter than the second phrase in the period. That is okay in contrasting periods, since the phrases should be different from each other anyways!

A modulating period occurs when the second half of a period differs from the first half in terms of its key. The period starts in the tonic key and modulates to another key, usually the dominant key, and then returns to the tonic key. This creates a sense of tension and resolution and is commonly used in classical music. The modulating period is different from the "closed period," where the phrase ends with a cadence in the tonic key.

If you want to see an example of a modulating period, you can see the excerpt from Beethoven’s Appassionata Sonata in F minor above.

Asymmetrical periods consist of three or five phrases. They are asymmetrical in that the number of antecedents will be different from the number of consequents. Chopin uses this technique quite a bit in his Prelude in C minor. Listen to it here and see if you can identify the asymmetrical periods.

Of all of the types of periods that you will come across in music theory, the double period is probably the most important to know and remember. A double period is made up of a minimum of four phrases, divided into two groups, the antecedent and the consequent. The first two phrases belong to the antecedent group, while the final two phrases form the consequent group which concludes with a cadence that responds to the less definitive cadence at the end of the antecedent group.

A common melodic pattern in a double period is abab' (four phrases), which is referred to as a "parallel double period" because the antecedent and consequent groups both start with the same melody.

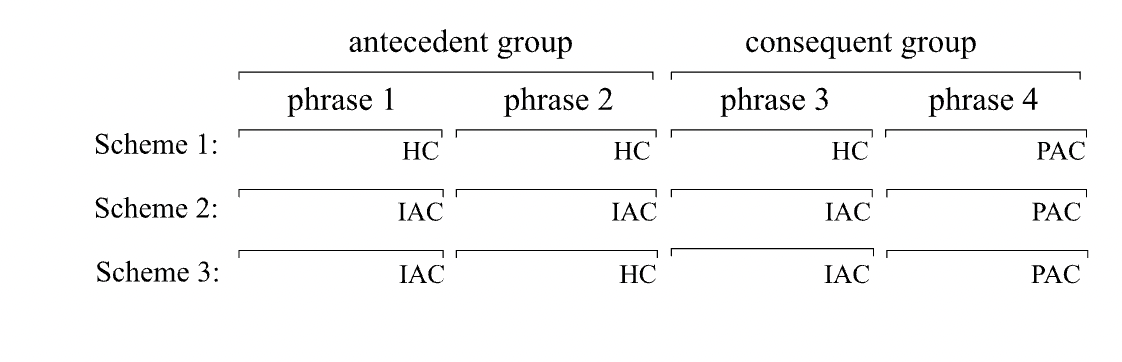

There are a few different permutations of cadential schemes in a double period. There are three main possibilities:

Image via Open Music Theory

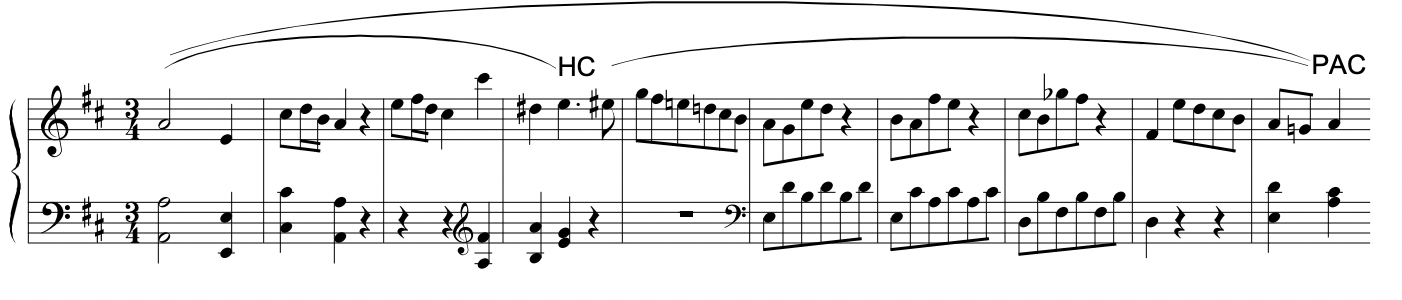

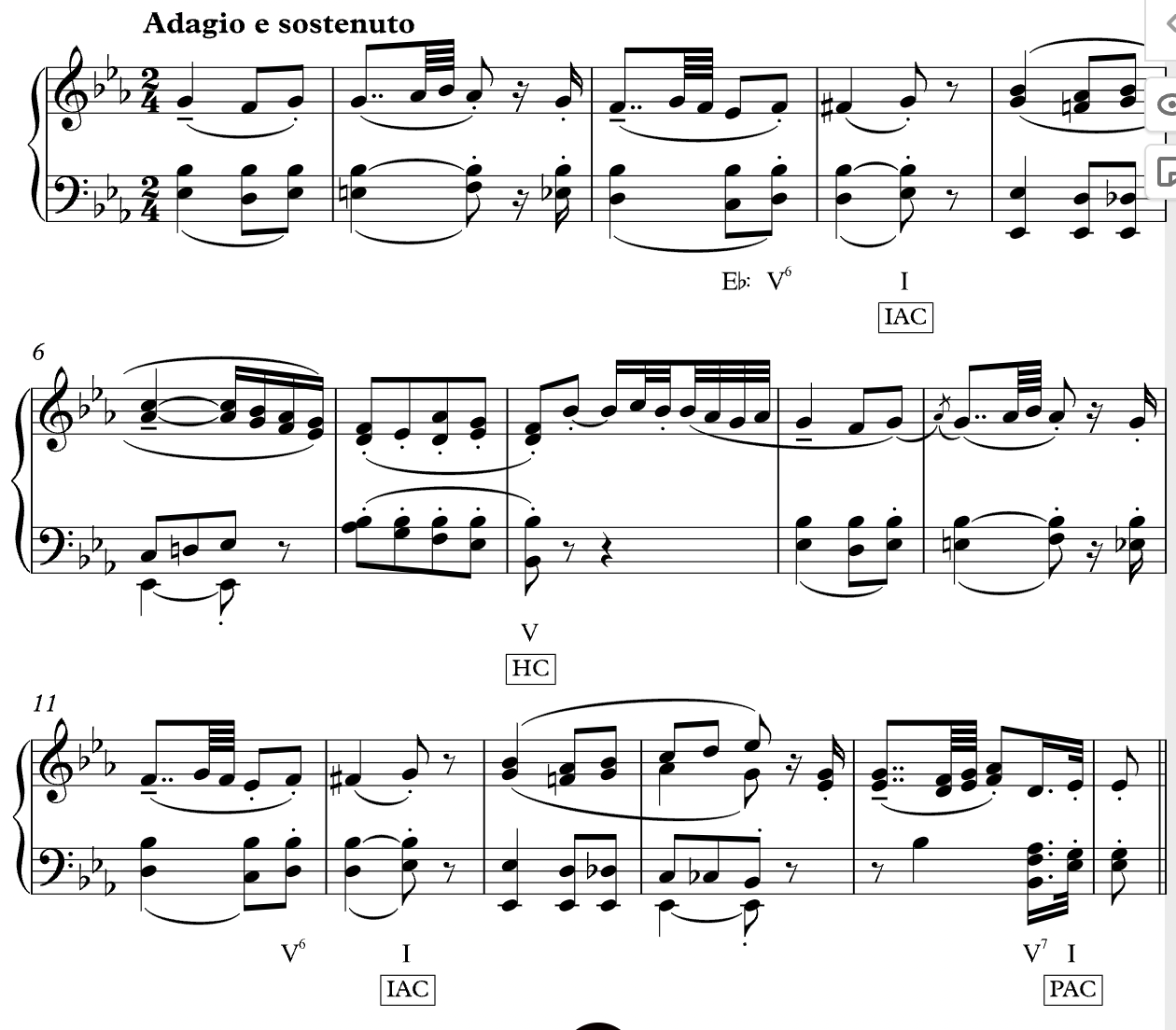

Here is an example of a double period from Kuhlau’s Piano Sonatina in G major (Op. 20, No. 2)

Image via https://milnepublishing.geneseo.edu/fundamentals-function-form/chapter/35-sentences-and-periods/

This excerpt shows a double period with the first half having two phrases as the antecedent and the second half having two phrases as the consequent. The first eight measures are comprised of two phrases, with an Imperfect Authentic Cadence (IAC) in measure 4 and a Half Cadence (HC) in measure 8. The following eight measures repeat the same pattern until measure 14, where the music changes direction towards a Perfect Authentic Cadence (PAC) in measure 16.

© 2024 Fiveable Inc. All rights reserved.