<< Hide Menu

Caleb Lagerwey

Robby May

Caleb Lagerwey

Robby May

Introduction

In the 1890s, American public opinion was being swept by a growing wave of jingoism – an intense form of nationalism calling for an aggressive foreign policy. As nationalism grew and European powers quickly engaged in imperialism, Americans wanted a piece of the pie. While Europeans focused their efforts on Africa and East Asia, the majority of American imperialism took place in the Caribbean, South America, and Polynesia. US Imperialism began formally following the Spanish-American War, a war in which the United States founded much of its overseas empire. This guide will go over the causes of the Spanish-American War and the outcomes that eventually led to growth in American foreign policy.

The Cuban Revolt

Because the US saw Latin America and the Caribbean as its zone of authority (Monroe Doctrine, anyone?), the US was growing increasingly uneasy about the Cuban rebellion against the Spanish. Cuba was close to Florida and a frequent target of covetous businessmen who envied its agricultural production of sugar and other tropical crops.

A Cuban rebellion formed against the Spanish, which began to sabotage and laying waste to Cuban plantations. They used a hit and run scorched earth policy to force the Spanish to leave. They hoped to either force Spain’s withdrawal or pull in the US as an ally. In response, Spain sent autocratic General Valeriano Wyler and over troops to crush the revolt. Valeriano Weyler y Nicolau, also known as "The Butcher," was a Spanish military officer and politician who served as the Governor-General of Cuba from 1896 to 1898. He is infamous for his brutal tactics during the Cuban War of Independence, including his policy of reconcentration, in which he forcibly relocated Cuban civilians into camps in an effort to quell the rebellion. Weyler's actions were widely criticized and were used as propaganda by yellow journalists in the United States to drum up support for the Spanish-American War.

He was relentless and brutal. He gave the rebels 10 days to lay down their arms.He then put into effect a “Reconcentration” policy designed to move the native people into camps. In these areas, Cubans died by the thousands, victims of unsanitary conditions, overcrowding and disease. He forced civilians into armed camps, where tens of thousands died of starvation and disease, and gained him the title of “The Butcher” in the American press.

Valeriano "The Butcher" Weyler

Yellow Journalism

To keep an eye on the Spanish, President William McKinley sent the battleship USS Maine to Havana harbor (Cuba’s capital city). While it was docked there, it blew up during the night. Although investigations decades later suggest it was likely an accident, the US blamed Spain, aided by war fever whipped up by Yellow Journalism, which refers to the use of exaggerated or falsified news stories aimed at increasing circulation of newspapers. Yellow journalism was often associated with the newspaper wars between Joseph Pulitzer's New York World and William Randolph Hearst's New York Journal

Image Courtesy of Wikimedia

The US war cry was “Remember the Maine; to hell with Spain!” Pro-imperialists like Theodore Roosevelt also cried for war, citing the Maine incident as an excuse to pursue the agenda they’d wanted all along. "Blame the Maine on Spain!" was another popular rallying cry.

The DeLome Letter

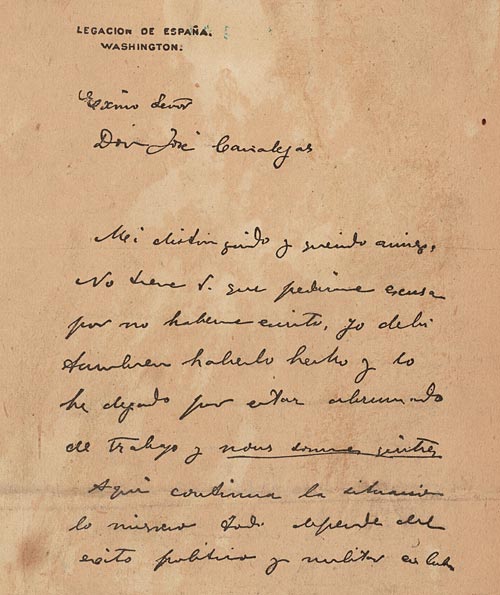

The De Lome Letter was a significant event in the lead up to the Spanish-American War. It was a private letter written by Enrique Dupuy de Lome, the Spanish ambassador to the United States, to a friend in which he referred to President William McKinley as "weak" and "a would-be politician." The letter was stolen and published in the New York Journal on February 9, 1898, causing outrage among Americans. The letter became a rallying point for those who favored going to war with Spain and further fueled tensions between the two countries. Ultimately, the publication of the De Lome Letter played a role in the United States' decision to declare war on Spain in April 1898.

The De Lome Letter

McKinley Declares War

Following the sinking of the Maine, McKinley issued an ultimatum to Spain demanding that it agree to a ceasefire in Cuba. Spain agreed to this demand, but US newspapers and a majority in Congress kept clamoring for war.

McKinley yielded to public pressure and sent a war message to Congress. He offered four reasons for the US to intervene in the Cuban revolution on behalf of the rebels.

- Put an end of the starvation and horrible miseries in Cuba

- Protect the lives and property of US citizens living in Cuba

- End the serious injury to the commerce, trade, and business of the American people.

- End the constant menace of peace arising from disorder in Cuba.

On April 25, 1898, McKinley formally declared war against Spain, beginning the Spanish American War.

Teller Amendment

Responding to the president's message, Congress passed a joint resolution on April 20 authorizing war. Part of the resolution was the Teller Amendment, which declared that the US had no intention of taking political control of Cuba and that, once peace was restored to the island, the Cuban people would control their own government. The Teller Amendment was modified by the Platt Amendment, which stipulated conditions under which the US would leave Cuba. It also permitted extensive U.S. involvement in Cuban international and domestic affairs for the enforcement of Cuban independence.

A political comic extolling US imperialism following the Spanish-American War.

The Aftermath

The US then took over a few islands in the Pacific and Caribbean, the most notable being the Philippines, Guam, Cuba, and Puerto Rico. The US also took over Hawaii for good measure since it was a source of sugar, pineapple, and another coaling station on the way to the Philippines. The Philippines themselves were a handy coaling station and stop on the way to China, a potentially huge market into which US producers were eager to get involved.

The Filipino nationalists that had partnered with the US to defeat the Spanish wanted independence, but the US (super patronizingly) didn’t think they were ready for self-rule, and pretty soon fighting broke out. The Filipino-American War officially lasted until 1902 and took the lives of thousands of soldiers and civilians on both sides.

The Filipinos used guerilla tactics to resist the better-equipped US military, so the US responded with horrific tactics including a early version of water-boarding and anti-civilians measures that killed upwards of 200,000 people. It was a nasty war that showcased the worst downsides of US imperialism. (Think overseas Indian wars)

Once the US had control over Hawaii and the Philippines, it became increasingly active in Asia, including engaging with China through helping other European powers put down the anti-Western Boxer Rebellion in 1899. The US also supported the so-called Open Door policy in China so that countries like the US were free to trade with China without interference from European powers.

Diplomacy of the Period

In the Caribbean and Latin America, the US began to assert its dominance much more heavily after the war. When Theodore Roosevelt was president--1901-1909--he came up with the Roosevelt Corollary to the Monroe Doctrine, which stated that not only should Europe stay out of the Western Hemisphere, but also that the US had the right to intervene if countries misbehaved as a way to prevent European intervention from becoming necessary.

A group of Japanese investors wanted to buy a large part of Mexico’s Baja Peninsula, extending south of California. Fearing that the Japanese government was scheming to secretly acquire the land, Lodge introduced, and the Senate agreed in 1912, a resolution known as the Lodge Corollary to the Monroe Doctrine. It stated that non-European powers (such as Japan) would be excluded from owning territory in the Western Hemisphere.

President’s Foreign Policy

| Roosevelt’s Big Stick Diplomacy | Teddy Roosevelt had once said that is was his motto to “speak softly and carry a big stick”. He built the reputation of the US as a world power and imperialists applauded his every move. |

| Taft’s Dollar Diplomacy | Taft depended more on investors’ dollars than on the navy’s battleships. His policy of promoting US trade by supporting American enterprises abroad was known as dollar diplomacy. |

| Wilson’s Moral Diplomacy | Wilson pushed for a moral approach to foreign affairs. He opposed imperialism and the big stick and dollar diplomacy policies of his Republican predecessors. Wilson believed in a principled, ethical world where militarism, colonialism and war were brought under control. |

© 2024 Fiveable Inc. All rights reserved.