<< Hide Menu

8.6 Early Steps in the Civil Rights Movement (1940s and 1950s)

7 min read•june 18, 2024

Dalia Savy

Robby May

Dalia Savy

Robby May

The Reconstruction era, which followed the Civil War, promised to bring political and economic rights to African Americans, but these promises were largely unfulfilled. The 13th, 14, and 15th Amendments were initiated into the Consitution, but society continued to find loopholes in them and racial inequality remained.

Truman and Civil Rights

Truman was the first modern president to use the powers of his office to challenge racial discrimination. The president used his executive powers to establish the Committee on Civil Rights in 1946. The committee was tasked with investigating and making recommendations on ways to end discrimination and promote civil rights. The committee's report, issued in 1947, called for a number of measures to address racial discrimination, including the elimination of the poll tax, the end of lynching, and the desegregation of the armed forces. He also strengthened the Civil Rights Division of the Justice Department, which aided the efforts of Black leaders to end segregation in schools.

In 1948, he officially ordered the end of racial discrimination throughout the federal government including the armed forces. Truman urged Congress to create a Fair Employment Practice Commission that would prevent employers from discriminating against the hiring of Black people, but Southern Democrats blocked the legislation.

Emmett Till

In the summer of 1955, Emmett Till left his home in Chicago to visit his uncle and cousin in Mississippi. Till, who was only 14 years old at the time, and a group of teenagers entered Bryant's Grocery and Meat Market to buy refreshments. Till purchased bubble gum, and in later accounts he was accused of either whistling at, flirting with, or touching the hand of the store's white female clerk—and wife of the owner—Carolyn Bryant.

In the middle of the night, Till was kidnapped and murdered by Bryant's family. They then beat the teenager brutally, dragged him to the bank of the river, shot him in the head, tied him with barbed wire to a large metal fan, and shoved his mutilated body into the water. Three days later, his corpse was pulled out of the river.

Till's body was shipped to Chicago, where his mother opted to have an open-casket funeral with Till's body on display for five days. Thousands of people came to the Roberts Temple Church of God to see the evidence of this brutal hate crime.

Till's mother said that despite the enormous pain it caused her to see her son's dead body on display, she opted for an open-casket funeral in an effort to "let the world see what has happened because there is no way I could describe this. And I needed somebody to help me tell what it was like."

The murder and subsequent trial of Till helped to galvanize the Civil Rights Movement, and the image of his open casket funeral was widely disseminated and helped to build support for the Civil Rights Movement.

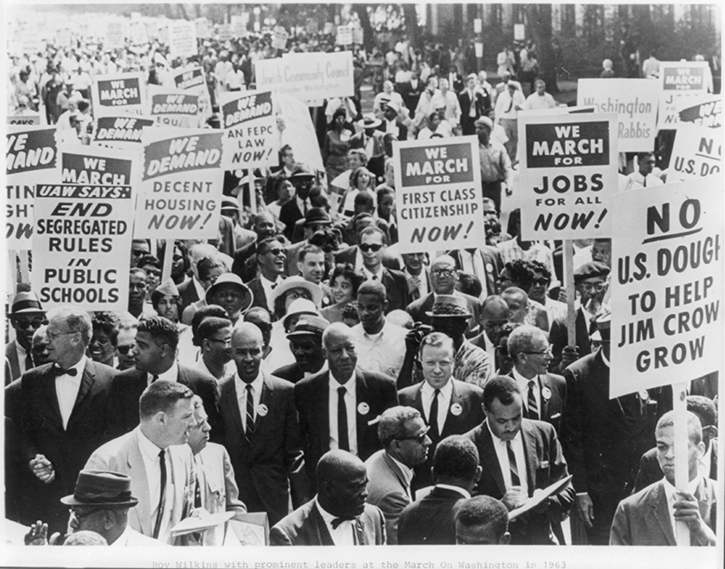

The NAACP

The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) is a civil rights organization in the United States that was founded in 1909. The organization is dedicated to fighting racial discrimination and working to secure political, educational, social, and economic equality for African Americans and other marginalized communities.

Image Courtesy of Library of Congress

Desegregating Schools

In addition to arguing that segregation was morally wrong, the NAACP argued that separate schools were psychologically damaging to Black children. In an experiment, when Black children were shown two dolls identical except for their skin color and asked to choose the “nice doll,” they chose the light-skinned doll. When asked to choose the doll that “looks bad,” they chose the dark-skinned doll. With these results, the NAACP argued that the segregation system caused feelings of inferiority in Black children. Attorneys then sought reliable plaintiffs who could withstand the racist intimidation and reprisals that followed the filing of the lawsuit.

The NAACP had been working through the courts for decades trying to overturn the Supreme Court’s 1896 decision, Plessy v. Ferguson, which allowed segregation in “separate but equal” facilities. After this lawsuit, they searched carefully for a case to challenge legal public school segregation and selected the case of Linda Brown. She was an African American student in Topeka, Kansas. At the time, the city had a system of racially segregated schools, and Brown was denied enrollment at an all-white school near her home. This made her required to attend a segregated school.

Brown v. Board of Education

In the case, Brown v Board of Education of Topeka, Kansas, a team of NAACP lawyers led by Thurgood Marshall, argued that segregation of Black children in public schools was unconstitutional because it violated the 14th Amendment’s guarantee of “equal protection of the laws.”

Image Courtesy of Harvard University

In May 1954, the Supreme Court overturned the Plessy case. Writing for a unanimous decision for Brown's case, Court Chief Justice Earl Warren ruled that:

- Separate facilities are inherently unequal and unconstitutional

- School segregation would now end A year later after many schools had not desegregated, the Court ordered the lower courts to proceed with “all deliberate speed” to desegregate public schools in Brown II.

Resistance in the South

Opposition to the Brown decision erupted throughout the South. To start with, 101 members of Congress signed the “Southern Manifesto.” This document was a statement of opposition to the Court's decision and a pledge to resist the integration of schools and other public facilities in all the legal ways possible. Those that signed the Manifesto argued that the Court's decision was a federal overreach and an infringement on states' rights. Many Southern states fought the decision in several ways, including the temporary closing of public schools and setting up private schools.

**The Southern Manifesto was a document denouncing the ruling and promising to use all legal means to maintain “separate but equal” as the status quo and condemning the Supreme Court for a ”clear abuse of judicial power.” **

School boards found a variety of ways to evade the Court's ruling. The most successful way was via pupil placement laws. They enabled local officials to assign individual students to schools on the basis of scholastic aptitude, ability to adjust, and “morals, conduct, health, and personal standards.”

Racism on the Road

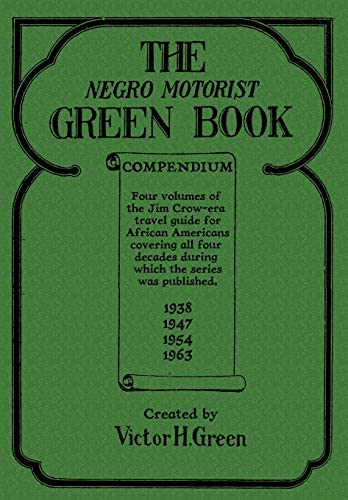

The Green Book

Black people faced many dangers and inconveniences when traveling the highway system. In response, Victor Green, a postal worker from NYC, wrote The Negro Motorist Green Book, also known as The Green Book.

Image Courtesy of Amazon

The Green Book was a guidebook that listed hotels, restaurants, service stations, and other businesses that were considered "friendly" to Black travelers, as well as safe places to stop and rest. Green eventually expanded its coverage from the New York area to much of North America, as well as founded a travel agency to help the Black community plan and book their travels.

The Montgomery Bus Boycott

In 1955, as a Montgomery, Alabama, bus took on more white passengers, the driver ordered a middle-aged black woman to give up her seat to one of them. Rosa Parks refused and her arrest for violating the segregation law sparked a massive African American protest in the form of a boycott of the city buses. These civil rights protests, called the Montgomery Bus Boycott, lasted for 385 days from December 1, 1955, to December 20, 1956, in Montgomery, Alabama. The boycott was organized by a coalition of African American leaders, including Martin Luther King Jr., and called for the desegregation of Montgomery's buses and the end of discriminatory practices against Black riders.

The boycott eventually led to a Supreme Court ruling, which declared that Montgomery's bus segregation laws were unconstitutional. It also served as an inspiration for other civil rights protests that reshaped America over the coming decades.

Image Courtesy of Newspaper

Martin Luther King Jr.

The Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., minister of the Baptist church where the boycott started, soon emerged as the inspirational leader of a nonviolent movement to end segregation. King’s voice became familiar to the entire nation.

Unlike many African American preachers, he never shouted, but captured his audience by presenting his ideas with both passion and compelling cadence. King claimed the idea of passive resistance or peaceful nonresistance. He told protestors in Montgomery, “If cursed, do not curse back. If struck, do not strike back, but evidence love and goodwill at all times.”

Nonviolent Protests

The Southern Christian Leadership Conference

In 1957, Martin Luther King Jr. formed the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC), which organized ministers and churches in the South to get behind the civil rights struggle. It aimed to use the moral authority and organizational resources of the churches to promote civil rights.

Sit-Ins

On February 1st, 1960, four African American college students in Greensboro, North Carolina, began a sit-in protest at a Woolworth's lunch counter, which was a part of a national chain of five-and-dime stores that refused to serve Black customers. The four students, Ezell Blair Jr., Franklin McCain, Joseph McNeil, and David Richmond, sat at the counter and ordered coffee, but were refused service. They returned to the store the next day with more students and began a sit-in protest that lasted for several weeks.

This sit-in started the sit-in movement and it is important to note that they were peaceful, following MLK's model of peaceful nonresistance.

To call attention to the injustice of segregated facilities, students would deliberately invite arrest by sitting in restricted areas.

The Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee was formed a few months later to keep the movement organized. They would use these sit-in tactics to integrate restaurants, hotels, buildings, libraries, pools, and transportation throughout the South.

© 2024 Fiveable Inc. All rights reserved.